“Spirit of Stonewall” Rally Kicks Off Queer Pride

Event Followed by Parade, Two-Day Festival

By MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

Under the slogan “Equality: No Turning Back,” San Diego’s 37th annual LGBT [Queer] Pride events kicked off with a sparsely attended “Spirit of Stonewall” rally on Friday night, July 28. Attendance at the much more popular parts of Pride weekend — the parade through Hillcrest on July 29 and the festival in the Marston Point area of Balboa Park off Sixth Avenue July 29 and 30 — was strong despite some concerns that the unseasonably overcast and humid weather might keep people away (it actually rained briefly the morning of the parade).

The Pride celebrations featured some political activism, mostly around the demand for marriage equality for same-sex couples, but it was also promoted as a major tourist attraction for San Diego, Mayor Jerry Sanders, who rode in the parade, told newscasters before the event that Pride brings in about $21 million to the city, much of it spent by Queer tourists attracted to San Diego for the event. The Friday night rally took place under a giant banner announcing that in the last 10 years Pride had raised an estimated $1 million for various Queer community organizations and causes.

The rally was hosted by Lesbian activist Laura Jean Willcock and opened with introductions of the Pride organization’s board chairs, Philip Princetta and Anne Hewett, Pride executive director Ron deHarte, board members, community notables and City Councilmembers Toni Atkins and Donna Frye. Atkins and Frye were there to present the annual proclamation from the City Council of “LGBT Pride weekend,” which hadn’t been forthcoming in 2005 even though Atkins had been the city’s interim mayor during the pride events.

The 2005 proclamation was withdrawn at the last minute following a controversy started by radical-Right activist James Hartline, a self-proclaimed “ex-Gay,” HIV-positive recovering crystal addict, who had looked up the names of all Pride’s 10,000 volunteers on a state database of registered sex offenders and found four people listed. Openly Lesbian San Diego County District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis refused to participate in the 2005 parade unless all the former sex offenders were removed from the volunteer rolls, and the Pride board decided to withdraw their application for a city proclamation.

This year, though Hartline and fellow radical-Right activists packed the final City Council meeting before the events and said that city sanction of LGBT Pride would encourage the spread of pornography, drug use and AIDS, the proclamation not only went through, it was passed unanimously. What’s more, the usual section to the side of the parade cordoned off for religious-Right protesters drew a far smaller crowd — less than 10 — than usual.

“We continue our fight for equality in the courts, legislatures and at the ballot box,” Atkins said at the rally. Citing the recent appointment of Traci Jarman to head the San Diego Fire Department, Atkins added, “Who would have thought that the city of San Diego would select a Lesbian as our new fire chief, and not only would her sexual orientation not be an issue in her selection, it was hardly mentioned except by our community.”

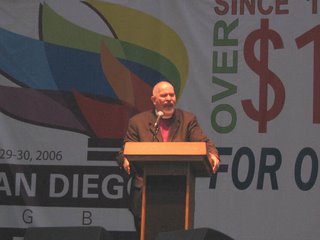

Atkins’ comments set the assimilationist tone for much of the rally, which featured four major speakers. First up was Rev. Troy Perry, who founded the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) in Los Angeles in 1968 after being kicked out of the Baptist ministry for being Gay. Perry built up the MCC into an international federation of nondenominational Christian churches that became the largest Queer organization of any kind in history. Though he recently retired as pastor of the L.A. MCC, Perry showed off in his speech at the rally that his “preacher chops” are alive and well, delivering a sort of secular sermon in the familiar rising and falling cadences of Baptist preaching.

Rev. Perry recalled an attack on the MCC in Atlanta, in which there were three attempts to burn the church down. When he went to Atlanta to see what he could do to help, he found the Atlanta Journal-Constitution had editorialized on behalf of the MCC members’ right to worship as they chose. What’s more, when he went to the church, “there were 40 butch dykes from the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Association, and they said, ‘We are here to make sure nothing happens to this church.’ Who would have thought that God would send his angels in the form of biker Lesbians?”

Another one of Rev. Perry’s anecdotes took his audience back to the early days of the AIDS epidemic, when the syndrome was still called GRID — Gay-Related Immune Deficiency — and he got his first phone call from a member of his congregation who had been diagnosed with it. In those days, he recalled, hospital staff members routinely put AIDS patients in isolation, left their food by the door of their rooms rather than entering with it, and dressed up in protective suits for fear of catching the syndrome casually.

When Rev. Perry first went to the hospital to see Dean, his sick parishoner, “he was isolated as if he’d been in a nuclear accident,” Perry recalled. They said I needed to wear a mask and hooded suit, and I said, ‘Dean doesn’t need to see me this way.’ I went in and hugged him for 15 minutes. He said he was going to die in six months and I told him, ‘Say with me: “You’re going to live with it, not die with it.”’ He told me he couldn’t get out of bed and the hospital refused to feed him. They left his food outside his door and wouldn’t bring it to him.”

Furious, Rev. Perry charged into the office of the hospital’s director and, waved in by a secretary who called him “Father Perry” — a mistake he didn’t bother to correct — “I told him, ‘I have a member of my church on the first floor and the staff won’t feed him. You don’t know much about publicity, but I’m telling you, I’m the one who can give it to you.’” According to Rev. Perry, from that time on the hospital’s attitude towards Dean turned 180°, to the point where when he was released he complained that the staff had been in his room with food trays so often — every two hours — he worried about getting fat. Dean lived four years after his initial hospitalization, and the last time he saw Rev. Perry he said, “You see, I lived with it. I didn’t die with it.”

Rev. Perry also told of his joy at the Queer community’s two big court victories in late 2003 — the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Lawrence v. Texas declaring sodomy laws unconstitutional and the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruling ordering that state to marry same-sex couples on the same basis as opposite-sex ones — as well as the legal victory for marriage equality in Canada, in a case actually filed by a Canadian MCC. “I told everyone I was going to marry Philip” (his partner), Rev. Perry recalled — then said he’d suddenly realized that the one person he hadn’t mentioned it to was Philip himself. After a classic movie proposal with Rev. Perry literally on bended knees in front of Philip asking him to marry him, the couple went to Canada despite warnings from reporters that they still wouldn’t be legally married in the U.S. Rev. Perry’s response paraphrased the famous National Rifle Association slogan: “They will take this ring off my cold, dead hand.”

Lavender Lens publisher and Lesbian activist and historian Bixi B. Craig had the unenviable task of following Rev. Perry. Craig’s talk was a surprisingly scholarly account of the evolution of the Queer struggle for equality from the early post-Stonewall days of “Gay liberation” into what she called “a more moderate, strategically rational movement.” Parts of Craig’s talk acknowledged more radical tendencies in the current Queer movement — including younger Queers’ growing tendency to reject the idea that they are “just like everybody else” and refuse to define themselves with hard-and-fast sexual orientations or gender identities — but most of her themes described a community becoming more integrated into the social norms.

“Our movement continues into the future with a ripening mood of integration into the popular culture,” Craig said. “We have learned to understand that spirituality is an integral part of people’s lives and our opposition is not rooted in church. … Another thing we have learned is that capitalism is not a bad thing after all. It has given us spaces in which to thrive: our own bars, restaurants, hair stylists and other businesses — and it has opened certain spaces for Gay and Lesbian life.” Craig described the marriage equality issue as a battle over “property rights” and the rights of same-sex couples to “procreate and raise children with the same rights as others, including full rights to adopt and foster.”

Craig wrapped up her speech with a laundry list of assimilationist demands: “Let Gay and Bisexual men have the same right to donate blood as everyone else [homosexually active men were barred from blood donations in the early 1980’s because of AIDS concerns and the ban remains in place to this day]. Let our military men and women serve not only proudly but openly as to who they are. Let our youth be guided in houses of education and everywhere else. Give same-sex couples the same access to the legal system as everyone else, not only marriage but family court and sexual-harassment litigation. Give us security in retail establishments. … As activists, we work for full LGBT rights in society. The language has changed but the message has not. Either we are fully equal or we are not.”

The following speaker was Neil Giuliano, former mayor of Tempe, Arizona and current executive director of Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), a nationwide organization which lobbies for positive depictions of Queers in the media. Giuliano said that he had come to a San Diego Pride event in 1996 and had been encouraged by the experience to come out as a Gay man. He joked that when he finally did so, early in his second term as Tempe mayor, the stories in the local papers began, “Ending years of speculation … ”.

“I really believe that the way the media portray our lives doesn’t make a bit of difference: it makes all the difference,” Giuliano said. “The visibility of our issues is greater than ever before. There is no turning back from the issues, and the way the media talk about those issues and frame those issues is very important. Public policy changes as public opinion changes. I share the frustration of activists that we haven’t won everything yet, but we have to balance the frustration with the strong successes we have had in just the last five years.”

Giuliano mentioned various issues GLAAD has been involved in, including the full-page “Marriage Matters” ads in the New York Times and other papers, which he said were actually started not by Queers but by straight allies, including the mayors of Salt Lake City and Boston. He also warned that, though polls show that young people are more sympathetic to Queer issues generally and marriage in particular than any older age group, we can’t take it for granted that they’ll stay that way.

“Our young people are being targeted by the fundamentalist religious Right,” Giuliano warned. “They’re going after them with targeted programs at high schools and colleges, and we’re creating a youth media program of our own aimed not only at LGBT but straight youth.” He also said that GLAAD is aiming another program at “people of faith and religion,” specifically at finding and highlighting the voices of “those who are in inclusive communities of faith.”

The final speaker was Juba Kalamka, African-American Gay activist and rapper with the Deep Dickollective, one of the leading groups in the so-called “homohop” movement of Queer and Queer-friendly rap. Alone of the speakers, Kalamka addressed the class issues of Queerdom as well as the racial ones, devoting most of his time to reading an intensely moving poem he wrote to the memory of Rocky Williams. Williams, a close friend and mentor of his in San Francisco, had headed the African Program of the STOP AIDS Project until his suicide July 24. According to Kalamka, Williams killed himself because he’d suffered financially, could no longer afford to pay San Francisco’s notoriously high rents, and had ended up homeless.

“This is the first time this has happened to someone who I was close to and who was as active as he was,” Kalamka explained. “I can’t leave without talking about him. Randy was not isolated in terms of lack of access to resources, but he was isolated in other ways. For me, it’s about remembering that because I don’t want to have to deal with that again.”