“Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man”: Mixed but Moving

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

You’ve probably heard Leonard Cohen’s music without knowing it. His songs have appeared in movies from McCabe and Mrs. Miller to the German film The Edukators and even (albeit in censored form) Shrek. They’ve been featured on TV shows ranging from The West Wing to The L Word — and Cohen actually did a guest appearance on Miami Vice, playing the head of Interpol. A native of Montreal, Cohen was born in 1934 and was a published poet before he graduated from college. He wrote the best-selling novel Beautiful Losers in 1966 and set out for New York to become a singer-songwriter because he figured singing his words would pay better than just printing them. While he never had much of a voice — something he’s refreshingly honest about; when he accepted a music award in Canada in 1992 he said, “Only in Canada could somebody with a voice like mine win ‘Vocalist of the Year’” — and other people’s records of his songs generally were bigger hits than his, he nonetheless built up a cult following with the release of his first album, Songs by Leonard Cohen, in 1967.

Discovered by the legendary producer John Hammond — who’d also helped launch the careers of Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, George Benson and Bruce Springsteen — and signed by him to Columbia Records, Cohen emerged as a kind of anti-Dylan. While even the most intimate of Dylan’s songs drew on phantasmagorical imagery and seemingly immense casts of characters, Cohen’s focused laser-like on the emotions of individuals or couples. Cohen also avoided writing openly political songs and, unlike Dylan, kept his original Jewish name. Though Cohen’s popularity dwindled in the 1970’s — especially after his ill-advised decision to do an album with baroque “Wall of Sound” producer Phil Spector, Death of a Ladies’ Man, at the height of the disco and punk movements — interest in his music began to perk up in the 1990’s after the late Kurt Cobain mentioned him in a song on his band Nirvana’s last album in 1993. Within two years there were at least two tribute albums to Cohen on the market and his songs once again began to attract the attention of record buyers — especially in Europe, where he’s always been more popular than in the U.S.

Alas, Cohen himself wasn’t around to share in the new-found acclaim, or the money it was bringing in; he’d deserted the music business to become a Buddhist monk and was living in a monastery on top of Mt. Baldy, taking care of his guru, a 90-something monk named Roshi. He gave his then-manager, Kelley Lynch, power of attorney over his business affairs, intending that she should run his publishing company and hold his royalties for him. Instead, he later alleged in a lawsuit, she sold the rights to his songs and pocketed the money herself, leaving him with $150,000 after a career that had earned millions. When he emerged from seclusion he made two new albums, Ten New Songs (2001) and Dear Heather (2004), produced and co-wrote the Blue Alert album for his current girlfriend, Anjani Thomas, and hired a new manager who, with producer Hal Willner, organized tribute concerts called Came So Far for Beauty in New York, Britain and Australia.

The new film Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man tells at least part of this story, though it tells it surprisingly obliquely. It’s basically documentary footage and interviews with Cohen himself intercut with other musicians — including Bono and The Edge from U2 — talking about how great he is and how much he influenced them, and footage from the Came So Far for Beauty concert in Sydney, Australia in 2005. Cohen, his speaking and singing voices both reduced to a monotone croak, gives anecdotes about his life but dresses them up in the same philosophical and imagistic language with which he writes his lyrics. The concert participants are an incestuous lot of currently popular “folk” singers — including brother and sister Rufus and Martha Wainwright and their mother and aunt, Kate and Anna McGarrigle — along with Teddy and Linda Thompson and a group called “The Handsome Family” and such unrelated people as rocker-turned-folkie Nick Cave, Antony (an androgynous singer from Britain who leads a band called Antony and the Johnsons), Beth Orton, Jarvis Cocker, Julie Christensen, Perla Batella and Joan Wasser.

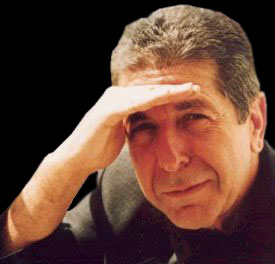

Though the grace and power of Leonard Cohen’s work and personality ultimately shine through, Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man is a film with enough flaws you could probably nit-pick it to death. The talking-heads footage and the concert scenes blend oddly together. The interview segments show a pockmarked Cohen in close-up, his face looking every bit as old as his birth certificate tells us he is — though, oddly, they seem to be the product of more than one interview: when Cohen discusses his monastery life, he’s wearing a thin beard he doesn’t have in the rest of the film.

The performances range from profoundly moving — Antony’s weird countertenor voice and feminine appearance (he looks like a drag queen doing Janis Joplin, appropriately enough since Cohen had a brief affair with the real Joplin) vividly project the song “If It Be Your Will” — to awful. Nick Cave and two female singers who don’t even begin to blend with him ruin Cohen’s most famous song, “Suzanne,” and Beth Orton simply sounds incompetent on “Sisters of Mercy.” Rufus Wainwright’s contributions are strong but a bit prissy — given his well-known homosexuality, the description of the blow job Cohen got from Joplin in “Chelsea Hotel No. 2” seems Gay when Wainwright sings it — though the less well-known Teddy Thompson does well by “Tonight Will Be Fine.”

It’s no surprise that the best version of a Cohen song in the film comes from Cohen himself. After Bono tells us that his all-time favorite Cohen piece is “Tower of Song,” there Cohen is singing it, in a sequence shot in a New York nightclub without an audience, with U2 as his backup band. Bono plays an electronic keyboard and sings harmonies, taking over the lead vocal for a few lines. The feeling is uncannily close to that of “The Wanderer,” the piece Johnny Cash recorded with U2 in 1993; like Cash, Cohen comes off as an aging bard who’s just returned from a long journey to tell his young acolytes the lessons he’s learned on his trek through the world.

In essence, that’s the overall message of Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man. Cohen emerges as a sort of wise man — the horrible naïveté that cost him his life savings is discreetly unmentioned — and his lyrics, dense and rich in poetic and philosophical musings on his own and other people’s emotions and behavior, are certain to affect you. Whatever might be wrong with this or that interpretation of a Cohen song in the film, the basic strength of his material comes through — and so does the love the musicians and performers in the film have for it, even though some of them love Cohen’s songs not wisely but too well. Leaving the theatre, you’re likely to be moved and feel exalted by an hour and 38 minutes spent with a fascinating man who’s created compelling art in three media — music, poetry and drawing — and you’re also likely to be tempted to empty your wallet to stock up on Leonard Cohen CD’s.

Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man is now playing at the Landmark Cinemas, 3965 Fifth Avenue in Hillcrest. Please call (619) 299-2100 for showtimes and other information.