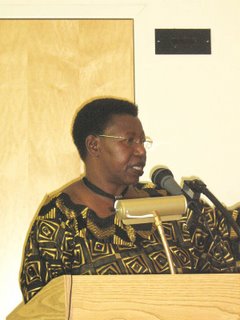

Former Ugandan Parliament Member Speaks in Mission Valley

Speaker Aggressively Discusses Women, AIDS and So-Called “Genocide” in North

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

“There has been a betrayal of women’s rights in Uganda,” said Miria Matembe, former ethics minister and member of parliament in the Ugandan government, in a speech at the Mission Valley public library July 2. Matembe, a heavy-set woman with a short, almost masculine haircut, spoke for well over two hours, fielding some surprisingly hostile questioning from the audience as she explained why she broke with Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, in 2003 after Museveni had Uganda’s constitution amended so he could run for a third term as president.

After noting that her friend, university professor Dr. Dee Aker, had last been in Uganda in 2001 and had observed the local elections that year — “they were very bad in my constituency of Barrera, and Dee said this was a hopeless case” — Matembe said she had defended the elections and the Museveni government. After 2003, Matembe changed her mind. “I had no choice but to part company with President Museveni and join those who think he’s taking us in the wrong direction,” Matembe said. “In 2003 I told him not to amend the constitution to eliminate the term limits. … Some African brothers, when they get into power, they cannot get out.”

Matembe joked that “one day we might have to come observe your elections to make sure they are free and fair,” but said that at least the United States has a tradition of checks and balances, including limits on the power of the president, that doesn’t exist in most African countries. She claimed that only two post-independence leaders in sub-Saharan Africa — Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Nelson Mandela of South Africa — have ever voluntarily stepped down from the presidencies of their countries. (A few audience members offered the names of one or two more.) “The others,” said Matembe, “hold ‘elections’ as personal property, view government as patronage and just stay around.”

Yoweri Museveni became the leader of Uganda in 1989, after a decade-long guerrilla war between his New Resistance Movement (NRM) and the Ugandan government. Prior to then, Uganda had been under the leadership of two bloodthirsty dictators, Milton Obote and Idi Amin. Amin had overthrown Obote; Obote in turn overthrew Amin in the 1970’s and ruled until the NRM won its guerrilla war and Museveni assumed power. At first Museveni promised a democracy and recruited political activists, including Matembe, to draft a new constitution.

“In the Ugandan constitution, we said, ‘No traditional chiefs,’ because they rule forever,” Matembe recalled. “So we put down a limit of two five-year terms for the president.” After questioning why the U.S. continues to support Museveni and hail him as a democrat even as his rule becomes increasingly dictatorial and corrupt, Matembe said, “I believed in that man until I saw him stand up in 2003 and say, ‘I would advise you to give up the term limit.’” Matembe explained that she had other issues with Museveni besides his scrapping the constitutional term limit to keep himself in office — notably her frustration at being unable to get him or the Ugandan parliament to live up to the constitutional guarantees of gender equality — but the term-limit issue was the last straw.

“We are just there … ”

“I wanted to use politics to espouse my cause for women’s equality,” Matembe said. “When the NRM came to power, it seemed to be a period of cleaning up. I wanted a legal framework to promote gender equality and empowerment for women’s. I linked with women in non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) to encourage change.” Among her greatest victories was a constitutionally mandated quota of at least 28.8 percent women in the national parliament and at least 30 percent women in the local and regional governments — but Matembe has become discouraged about that, too, feeling that the quota system has become an impediment to real progress for women in Uganda.

“We are just there; we got access and presence, but no influence,” Matembe explained. “We participated in vain, because at the end of the day our rights are not there. Women supposedly play an important role in Ugandan politics, but many decisions that affect women’s lives are still made without their participation. This is not only unfair and unjust, it renders the political process a sham.” What’s more, she said, the quota-guaranteed seats in the parliament have attracted women who are more interested in the income and perks of legislative service —especially desirable in a country whose economy is still underdeveloped and few middle-class jobs exist — than in activism. “They perceive [the quota system] as an act of privilege and generosity on the part of the government, so they are not willing to rock the boat,” Matembe explained.

According to Matembe, the biggest specifically feminist issues facing Ugandan women are property rights, divorce and domestic violence, including sexual abuse. While the Ugandan constitution says at least some of the right things on paper — “it does away with traditional practices [like arranged marriages and female genital mutilation], sets the marriage age at 18 and grants women the right to own property independently of their husbands” — the government “has been very reluctant to make laws in conformance with the constitution on women’s rights,” she explained.

Rape Laws from 1908

What that means in practice is that rights American and other Western women won in the 1970’s after decades of feminist struggle (and which, as Matembe grimly noted, many young American women take so totally for granted that they refuse to organize to protect them) still don’t exist for women in Uganda. The laws governing rape and domestic abuse date back as far as 1908, when Uganda was still a British colony, and allow men accused of rape to use the victim’s previous sexual history in court against her. What’s more, they specifically define rape as a woman being forced to have sex against her will by a man other than her husband. Like most U.S. rape laws before the so-called “second wave” of feminist activism in the 1970’s, Uganda’s laws say that a husband has the automatic right to have sex with his wife any time he wants, whether she wants to or not.

The only change in Uganda’s rape laws since Museveni came to power has been to increase the penalties, as a response to the AIDS crisis — but even that is meaningless if women are too traumatized or scared by the court system to testify against their rapists, and according to Matembe that’s usually the case in Uganda today. What’s more, she added, even when rapists are convicted “the judges don’t put out big sentences. The [rape] laws are not user-friendly. They put the woman on trial and put her through a second rape in court.”

Matembe boasted that she had once suggested castration as an appropriate punishment for rapists — leaving it somewhat ambiguous whether she was serious or simply taking an extreme position to dramatize the importance of reforming Uganda’s antediluvian rape laws. (At least one woman in the front row at the Mission Valley library seemed to like the idea.) Matembe said “there is no political will” to change these ancient rape laws and that the entire promise Museveni made to be interested in women’s participation in government was a sham.

“He was using us to promote his causes,” she said. “The government is mainly interested in harnessing us to stay in power. Beyond that, the government is not interested in empowering women, as shown by its refusal to enforce the laws on equal property rights and enact new laws on divorce and sexual abuse.” About the only hope for Ugandan victims of rape or domestic violence, Matembe conceded, lies with non-governmental organizations like Hope After Rape and Action for Development, who reach out to the survivors of rape and domestic violence, respectively.

AIDS, Abstinence and Health Care

Asked about Uganda’s AIDS situation and alleged U.S. pressure on the Museveni government to abandon condoms and safer-sex education in favor of abstinence-only programs, Matembe said she’d been involved personally in Uganda’s AIDS response and took pride in the claim that Uganda’s rate of HIV seropositivity had fallen from 15 percent of the population in the early 1990’s to 6 percent today. “Our AIDS rate is low because of our own efforts, not the United States,” she said. “The U.S. government came to ‘help’ us with AIDS just to be seen. For America to put Uganda up as African’s model AIDS program was Bush’s idea, not ours.” She said that Uganda applauded the United Nations effort to set up a Global Fund against AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria (from which the U.S. has largely abstained in favor of setting up an anti-AIDS fund of its own) but said “we don’t need to borrow strategies from anywhere.”

Matembe said she personally took the HIV antibody test when she visited the U.S. in 1991 “because I wanted to be at the forefront in fighting the evil, and therefore I wanted to know my status. (This was in sharp contrast to South African president Thabo Mbeki, who refused to take the test in 2000 because, he said, it would be a gesture of support for the orthodox model that HIV is the sole cause of AIDS and he didn’t want to commit to that while he was inviting scientists with other points of view to advise him on the syndrome.) Matembe said the initial strategy of Uganda was to “take AIDS on at every function, including a funeral or a wedding … It was a tough journey, and we were abused for it. I talked at a wedding, and when the boy went to kiss the girl, the girl said, ‘Don’t! You’ll give me AIDS!’”

Instead of pushing abstinence-based anti-AIDS programs on Uganda, Matembe said the developed world would be better advised to work on improving Uganda’s overall health-care infrastructure. “If we had good health facilities, we would not be dealing with AIDS,” she said. “Caring for the sick without gloves, you get AIDS.” She also said that the abstinence-only proponents ignore both human nature and the lack of rights for women in Uganda — particularly the laws that prevent married women from refusing to have sex with their husbands or insisting on condom use when they do. “I am a very good Christian, but I am against the churches saying abstinence,” Matembe declared. “Even Jesus said that the spirit was willing but the body was weak. What about the bodies of ordinary human beings?”

Uganda’s North: Terror and Camps

Though much of Matembe’s presentation was fervent — she frequently raised her voice and gestured flamboyantly to make her points — on no other issue was she as emotional as on the situation in northern Uganda. A good many of the people in the audience, including some Ugandan émigrés, had been encouraged to come to the meeting by a local group called the Campaign to End Genocide in Uganda Now (C.E.G.U.N.). Their argument is that Museveni’s government is carrying on a campaign to wipe out the Acholi people of northern Uganda by placing them in concentration camps, and using the threat of a terrorist organization called the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) to justify keeping them in the camps.

Matembe couldn’t have disagreed more. Whatever her differences with Museveni on other issues, she remains a staunch supporter of his policies in the north, convinced that relocating the people out of their villages and into camps in the 1990’s was the only way to stop the LRA. She said the north had been “pacified” to the point where there is only one district — in the Chittagong/Gulu area — where the camps are still necessary. “Problems remain in Acholiland,” Matembe conceded. “Women have been raped. Young children have been abducted and raped and have had children by fathers they don’t know. The struggle has been going on for 20 years. It is very sad that that happened.”

But Matembe vehemently defended Museveni against the C.E.G.U.N. members’ charges of genocide. She blamed the LRA and its leader, Joseph Kony, for the brutalities in the north and the need to keep the Acholis in camps. “We debated it in parliament and tried our best, but we couldn’t sort out the situation or have talks with the terrorists,” Matembe said. “Kony has no agenda. The other groups who were fighting the government all had agendas, and we were able to negotiate with them and bring them into the government.” Matembe also blamed the government of Sudan, which until recently provided weapons and financial support to the LRA and still gives LRA fighters sanctuary in their country. (Ironically, Sudan’s Arab Muslim-dominated government has been accused of genocide against the Christian and animist people of southern Sudan as well as the people of Darfur in the west, who are Muslims but are Black instead of Arab.)

During the question-and-answer period, Matembe had to deal with hostile statements from the C.E.G.U.N. members and supporters in the audience, and at times it seemed as if the Black people in the room were applauding the C.E.G.U.N. speakers while the whites were coming to Matembe’s defense. A number of the C.E.G.U.N. members pointed to a recent interview Joseph Kony gave to the BBC after years of media silence, during which he identified the LRA as a movement for Acholi liberation and denied that his fighters ever cut off the limbs, noses or lips of fellow Acholis — as Matembe and the Ugandan government have charged.

Matembe responded furiously. “The people fighting Kony have told us what was going on, and one problem was that Sudan was arming them,” she said. “Kony is an animal. How come he turns his guns on the Acholi people and cuts them down instead of fighting against the [Ugandan] army?” Asked why the struggle in the north has been going on for over two decades, Matembe said, “Guerrilla wars take a long time to win. Even the U.S. hasn’t got Osama bin Laden and hasn’t stopped the situation in Iraq. Uganda is poor and is trying to fight with Kony.” Matembe did acknowledge that “the army in Uganda is corrupt,” and that one reason the war is lasting so long is that much of the money set aside to fight it is being diverted into the pockets of military leaders — some of whom received high-powered, high-paid appointments in Museveni’s government even after parliament censured them for corruption.

According to Matembe, it’s the overall poverty in Uganda, as well as the threat from the LRA, that’s keeping the Acholis in the camps this long. “People are in the camps because the government doesn’t have enough money,” she said. “We put a motion before the Ugandan parliament to have the north declared a disaster area so we could get foreign help, but Museveni was against it because he thought it was a sign of defeat.” One issue on which she and the C.E.G.U.N. people did agree was that after a decade in the camps — in which time a whole generation has been born and grown to adulthood without any formal education whatsoever — the Acholis would need a lot of physical, psychological and spiritual help to leave and resume any sort of normal life, and Matembe said she hoped the Americans would help provide that.

“It is not true that the government is deliberately exterminating the Acholis,” Matembe said. “Acholis do not live in Acholiland alone. We emigrate, we mix, we intermarry. I regret the situation in Acholiland today. It is my view that the war is no longer at that magnitude. It is now mostly in southern Sudan. I understand that the government has decided that these people should go out of the camps, but to do that these people must have a lot of rehabilitation, including psychological help and searches to find out if their original homes still exist. But I want to believe that something is being done for these people.” Denying the claims of C.E.G.U.N. and other groups that one million Acholis have been killed by the relocation, Matembe said, “I’m not there. I talk from my heart and I want to appeal to the people from Acholiland to be honest and not to tell Americans that one race in Uganda is trying to eliminate another.”