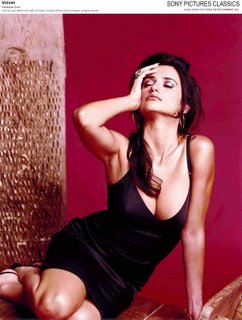

Almodóvar’s Volver: Modern “Women’s Picture”

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • Photo copyright © 2006 by Sony Pictures Entertainment, Inc. • All rights reserved

Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar has become a brand-name director, one of the few in movie history whose own name on a film can attract an audience no matter what the movie is about or who’s in it. (D. W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, Frank Capra, Alfred Hitchcock, Federico Fellini and Ingmar Bergman were brand-name directors for earlier generations of moviegoers.) His early features were nervy, polymorphously perverse tales drawing on his life as a Gay man and the cultural explosion in Spain called “La Movida” that followed the death of Right-wing Catholic dictator Francisco Franco in 1975. Then he followed the example of George Cukor and many other Gay filmmakers in cinema history and became a so-called “women’s director,” building his stories around female characters and performers in general and one especially powerful actress, Carmen Maura, in particular.

Almodóvar’s movies have actually ranged wildly between male and female leads. In Talk to Her (2002), the men were front and center and the women, though significant to the story, were literally “out of it,” locked in persistent vegetative states. Bad Education (2004) was an unexpectedly controversial return to Almodóvar’s Gay roots, a story about a Gay filmmaker and a straight actor who came to him with a film story based on dark secrets from both their pasts. While the Zenger’s review of Bad Education was headlined “Almodóvar Comes Home,” other critics got surprisingly huffy about it and questioned why a director who makes such superior films about women should suddenly feel compelled to make a movie about Gay men simply because he is one. (Aside: how, in a world in which Bad Education exists, something as one-dimensionally depressing as Brokeback Mountain could have been hailed as the greatest Queer film of all time beggars the imagination.)

Well, with Volver — a title that literally means “homecoming” or “return” — Almodóvar has given the critics and audience members who crave “women’s pictures” from him what they want. Indeed, men are so unimportant in this movie that the top-billed male cast member is seventh in the credits. It is a film about female solidarity and betrayal, and about issues of life and death. At times Almodóvar seems to be taking Bob Dylan’s line, “He not busy being born is busy dying,” literally in his script. It takes much of its inspiration from where it takes place: a particularly impoverished part of Spain called La Mancha, where Almodóvar was born and raised and whose high winds, in a popular Spanish superstition, are supposed to drive its people crazy. La Mancha is most famous in literature as the setting for Don Quixote, Cervantes’ famous tale about the wanna-be knight who fought windmills thinking they were dragons — and windmills, albeit the modern, high-tech kind, feature prominently in Volver as well.

Volver is a difficult film to review, not only because its plot is complex — “My films are becoming more and more difficult to tell and summarize in a few lines,” Almodóvar admits — but because so much of its appeal is based on wrenching surprises in its plot line that a reviewer doesn’t want to give away to potential audience members. Indeed, the biggest twist of all has so far been kept secret not only by the publicity department at Sony Pictures Classics, which released the film, but by everyone who’s written about it. The central character is Raimonda (a surprisingly restrained Pénelope Cruz), who grew up as an orphan when both her parents died in a fire. She lives in La Mancha, works in a failing restaurant, is married to a boor named Paco (Antonio de la Torre) and has a teenage daughter, Paula (Yohana Cobo), who’s just coming into her own sexually. Indeed, Paula has attracted pedophiliac and incestuous attentions from Paco, and when he finally makes a move on her she kills him with a kitchen knife, leaving her mom the task of cleaning up the mess and getting rid of the body.

The rest of Raimonda’s family is almost as dysfunctional. Her aunt Paula (Chus Lampreave), after whom she named her daughter, is living at home with such a bad case of Alzheimer’s that when Raimonda visits, Paula asks her why she’s no longer pregnant and when she had the baby. (The “baby” is a teenager already!) No sooner does Aunt Paula die than Raimonda’s long-dead mother, Irene (Carmen Maura), makes a reappearance, spending most of her time at the home of Raimonda’s sister Sole (Lola Dueñas). When she’s not hiding from Raimonda under Sole’s bed, Irene is hanging out in Sole’s living room, which doubles as the beauty salon that makes Sole her living, being passed off as a “Russian” and told not to open her mouth for fear her perfect Spanish will “out” her as a native. Also in the cast is Raimonda’s friend Agustina (Blanca Portillo), a short-haired, thin woman who’s ill with cancer. Thanks to Irene’s presence, Raimonda is confronted with some stark truths about her life that have been withheld from her for years, even as she discovers an amazing reservoir of inner strength symbolized by her ability to keep the restaurant open even though its formal owner walked away from it and just wanted to sell it.

Like most of Almodóvar’s films, Volver changes tone frequently. It opens with a scene of the women characters polishing graves — indeed, the film’s title and Almodóvar’s name are made to look as if they have been chiseled into monuments. Some of the graves are their ancestors’; some are their own, having been purchased and decorated with elaborate memorials in what the funeral industry euphemistically calls “pre-need buying.” Much of the byplay around Paco’s corpse evokes memories of Alfred Hitchcock’s mordant black comedy The Trouble with Harry (1955), and the music by frequent Almodóvar collaborator Alberto Iglesias strikingly resembles the scores Bernard Herrmann wrote for Hitchcock in the 1950’s. With Irene’s reappearance, the film becomes more intensely dramatic, with only Almodóvar’s astringent story sense keeping it from soap-opera sentimentality.

Much of the appeal of Volver comes from the natural, unforced performances Almodóvar gets from his actresses. Pénelope Cruz, who has generally looked out of place in American films, triumphs playing a woman of her own nationality and speaking in her native language; she even gets to sing the title song — a Spanish flamenco adaptation of an Argentinian tango — though her voice is dubbed by Estrella Morente. Carmen Maura has surprisingly little to do but does it well. Blanca Portillo is excellent as the family friend and cancer patient who refuses any hint of sympathy and offers a striking display of integrity towards the end of the film. Yohana Cobo is a striking-looking teenager who offers hints of great things to come; the film throws revelations at her and forces her to mature quite rapidly, and she handles a challenging role expertly. José Luis Alcaine’s cinematography is also welcome; how nice it is to see a movie in which the wide-screen shape is actually filled out and used creatively. How nice, too, it is to see color which actually serves the story instead of just being there because modern audiences expect it, and which encompasses more of the visible spectrum than just dirty browns and dank greens!

After the vivid brilliance of Talk to Her and Bad Education, the relatively softer, gentler Volver comes off a bit as Almodóvar Lite. Even its typically Almodóvaran plot twists come off this time as more mellow than wrenching, more a slow journey to understanding than the psychological roller-coaster rides of some of his earlier movies. But Almodóvar is so talented a filmmaker that even working below the peak of his powers, he’s still more talented than most other modern directors working at full steam. If you’ve liked Almodóvar’s previous films, or if you give a damn about the art of cinema and want more from a movie than spectacular computer-generated imagery and cardboard characters, you’ll enjoy Volver.

Volver is playing at the Landmark Cinemas, 3965 Fifth Avenue in Hillcrest. Please call (619) 299-2100 for showtimes and other information.