Cygnet’s Wonderful, Wonderful Copenhagen

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

On Sunday, September 25, 1941, Werner Heisenberg, the most prestigious and internationally regarded physicist left in Nazi Germany and the head of the Nazis’ atomic weapons program, traveled to Copenhagen in Nazi-occupied Denmark, ostensibly to lecture at a Nazi-dominated scientific institute in the city but actually to visit his old friend, colleague and mentor, Niels Bohr. Heisenberg stayed in Copenhagen one week and saw Bohr on at least three occasions, but on one of those meetings their conversation was so explosive that Bohr returned home angry and told his wife Margarethe that he never wanted to see Heisenberg again. Exactly what went on between them during that week is a secret both men took to their graves — though Heisenberg and Bohr each offered contradictory accounts of it in interviews, statements and letters after the war — but it was from this raw material that British playwright Michael Frayn fashioned his 1998 play Copenhagen, playing through September 24 at the Cygnet Theatre, 6663 El Cajon Boulevard.

Frayn’s script doesn’t offer his own re-creation of what happened that fateful evening in Copenhagen on which Bohr and Heisenberg went for a walk as bosom buddies and came back furious with each other. Instead it plays fast and loose with the time frame and even shows Bohr and Heisenberg continuing on with their arguments after both men and Bohr’s wife —a third on-stage character and frequently the voice of reason between them even though all she knows about science is what she’s picked up from the manuscripts she’s typed for her husband — are all dead. (It’s hard to believe that if there is an afterlife and Bohr and Heisenberg made it there, they wouldn’t spend at least part of their time trying to reason out the physics of their current state of existence and reconcile those with the discoveries they made in this world.)

What results is a marvelous, if rather talky, play about the obvious dilemma facing both the proudly nationalistic German Heisenberg and the half-Jewish Dane Bohr: how to reconcile one’s calling as a scientist with one’s duty as a human being, and whether scientists ought to be held morally accountable for the consequences of their discoveries and hold back from certain lines of research that might have destructive consequences. It’s also about more than that: it’s about the thickets of contradictions Heisenberg, whose greatest contribution to science was the discovery of the so-called “uncertainty principle” at the heart of quantum physics, created in his public statements about his wartime role, and the irony that a man famous for explaining the universe as based on “uncertainty” would leave behind so many uncertainties about himself. And it’s a script that questions the common notion that scientists do their best work in close collaboration, or at least communication, with each other; in one of Frayn’s quirkiest and most moving moments, both Heisenberg and Bohr admit that their greatest insights came to them while they were totally alone in isolated environments that gave them a chance to think without distractions.

Even before Frayn wrote his play, the Copenhagen meeting(s) between Heisenberg and Bohr had taken on an almost mythical significance in the history of World War II and the role atomic weapons played in it. In the late 1930’s, Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, both pacifists, Jews, and refugees from Nazi Germany, put aside their anti-war convictions and lobbied President Franklin Roosevelt to start a nuclear weapons program for fear that the Nazis were also working on such research — and if the Germans got the bomb before we did, given Hitler’s known record of brutality, he would use it to destroy whole cities, or even nations, and establish the “Thousand-Year Reich” of which he boasted. Ironically, Hitler’s bomb program was hobbled from the get-go by his racism; before Hitler took power Germany had been the world’s leader in theoretical physics — but most of those physicists were Jews and, smart enough to see the handwriting on the wall, left as soon as they could. Eventually most of the German physics community relocated to the U.S. and worked on the Manhattan Project, which gave the U.S. the world’s first nuclear weapon — and Bohr joined them as soon as he got out of Denmark in 1943, first to neutral Sweden and ultimately to the U.S.

Frayn takes all these facts and uses them to construct a somber, compelling meditation on the responsibilities of scientists, especially but not only in wartime. His play examines one of the great unanswered questions about Heisenberg — did he fail to build a bomb because he deliberately sabotaged the German nuclear program out of horror at what the Nazis would do with it, or did he simply get the science wrong and decide a bomb was impractical? It also questions whether Heisenberg, who confined his actual work to building an experimental nuclear reactor for energy and medical uses — though one which could also have made plutonium, which could have been used in a nuclear weapon instead of enriched uranium (and was in the bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima) — was really morally superior to Bohr, who did work on a weapons program that manufactured atomic bombs that were used to destroy two cities. The currency of these issues was hammered home when on August 26, the day Cygnet’s production of Copenhagen opened, the Associated Press announced that, dodging international attempts to stop them from enriching uranium, Iran was going to build a heavy-water reactor that would allow them to use ordinary, unenriched uranium to generate power — and to create plutonium to fuel a nuclear weapon. This is the same kind of reactor Heisenberg was designing for the Nazis.

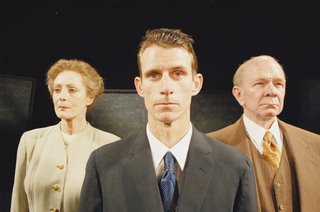

Cygnet Theatre gives Copenhagen a first-rate production. Jim Chovick stands out as Bohr; his age and overall appearance perfectly suit him to play an eminence grise but he’s also spry enough to catch the nervous, fidgety energy of a character who seems unable to sit still for more than a few seconds at a time. Rosina Reynolds as Margarethe turns out to be as good an actress as she is a director; superbly aged by Cygnet’s (uncredited) makeup artist, she’s not only effective as the materfamilias who holds her rambunctious, hot-tempered husband in place — in Frayn’s script Heisenberg calls their family an atom, with her as the stable nucleus and him as the randomly mobile electron — she also does a good job as the representative of all us non-scientists in the audience trying to make sense of what her husband and his equally abstruse friend are saying. Cygnet regular Joshua Everett Johnson is too young-looking for Heisenberg — one wouldn’t believe that this man turned 40 just three months after the Copenhagen meeting, and it seems odd that the makeup people who so effectively aged Reynolds didn’t give him a similar treatment — but otherwise his performance is great, ably portraying both Heisenberg’s misgivings and his rationalizations.

Director George Yé, faced with an unusually long (the first act is 80 minutes, the second an hour) script that’s basically three people talking in a room, solves the obvious problem of avoiding boredom by keeping the actors, Chovick especially, in almost constant motion and having them spit out Frayn’s dialogue so fast they have to lose themselves in their characters merely to keep up the pace. Yé also did his own sound design, which effectively mixes in music at the start and finish of each act — though the opening sound effect of Nazi forces marching through the streets of Copenhagen should have been “panned” across the theatre instead of remaining in one place aurally. The set by Sean Murray, Cygnet’s artistic director, is simple: just three chairs and a black backdrop in front of which are hung blackboards with mathematical equations — and lighting designer Eric Lotze creates a powerful effect towards the end when he uses the center blackboard as a screen on which to project the so-called “diffusion equation” which proved an atom bomb would work.

Copenhagen is a powerful drama that plays to the strengths of the Cygnet Theatre: incisive direction, strong character portrayals, excellent physical production. It’s not exactly a good-time piece, but it has its moments of humor. On opening night, when Bohr announced early on that he’d co-written a paper that conclusively proved it would not be possible to build an atomic bomb, the audience laughed at how wrong he turned out to be — but also with the mixed feeling of how much better off the world would have been if he’d been right.

Copenhagen plays through Sunday, September 24 at the Cygnet Theatre, 6663 El Cajon Boulevard, Suite N. Performances are at 8 p.m. Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, 2 and 7 p.m. Sundays. The Sunday, September 10, 2 p.m. show will feature a post-show discussion led by Herbert York, American nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project. Tickets are $25 Thursday and Sunday evenings, $27 Friday evening and Sunday matinee, $29 Saturday, and can be purchased by calling (619) 337-1525 x3 or online at www.cygnettheatre.com