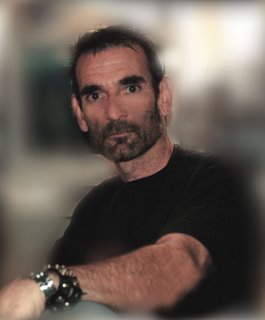

DAVID LAURITO:

Photographer Exhibits at Pleasures & Treasures Through Dec. 15

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • Photo by David Laurito, copyright © LP Communications/Laurito Photography, Inc. • All rights reserved

“My first dream was to be a musician, to write music and record and do all that,” photographer David Laurito said. But a circuitous route through life took him away from his artistic ambitions, threw him into the corporate world, then pushed him out again and into an artistic career in a different medium. Laurito’s works, on display at Pleasures and Treasures, 2228 University Avenue in North Park, through December 15 and on an ongoing basis at the Club San Diego bathhouse, 3955 Fourth Avenue in Hillcrest, run the gamut from non-explicit but intensely erotic male studies to shimmering landscapes and abstract patterns inspired by Japanese origami.

After a successful but unfulfilling stint as an electronics marketer — “I hated it, really hated it,” Laurito admitted; “Everybody in the whole corporate world is scary” — Laurito “went through a series of things,” he said. “I owned a CD store for a while, got out of the CD store and then started getting heavily into writing music.” Though he didn’t become a performing musician, he started developing a reputation as a composer and a record producer — and then his life got sidetracked yet again, this time when both his parents fell ill. Laurito put his own life on hold for “about three or four years” until his parents passed away — and then, looking for another way to make a living, he hooked up with a friend to start a company to make greeting cards for Gay men.

“At the time,” Laurito recalled, “there weren’t any — I wouldn’t say ‘Gay’ greeting cards, but male greeting cards, the kind of cards that I could give to my partner and not be embarrassed. I didn’t like the kind that had some naked guy on there that was disgusting. I wanted something that made some kind of deep sense, basically a male-to-male card like you would give to your wife, but between men.”

The original plan was that Laurito would run the business end of the enterprise and his friend would do the photography. “He was a photographer, but he was also in the corporate world,” Laurito said. “He was where I was 10 years before, caught in the middle.” Caught between the demands of his corporate job and the time needed to get a business off and running, Laurito’s friend bailed — and Laurito’s life partner Jimmy told him, “Why don’t you take the pictures?”

At the time, Laurito said, he’d been “basically fiddling around” with amateur photography for about 10 years, but “within a week or two I was taking cover shots. We would take the pictures and have them laminated right on the cards to give it a very hurried, one-of-a-kind type-ness, signing and numbering each card like a limited edition. Actually, we still do that now. One part of the company does that. We’ve got a good, solid base of people and companies I do Christmas cards for, and every year they want to know what picture they’re going to have. They get to pick one out from the Laurito Hall of Fame, and they’re really big on trees.”

Branching Out

Laurito’s next step into full-time photography took place on one of his frequent visits to Great Britain. “A couple of friends of mine there basically wanted someone to take portfolio pictures for them,” he recalled. “So I told them I’d do it for them.” Stewart, one of the friends who wanted Laurito to photograph him, hedged his bets by inviting another photographer to the same session.

“This other photographer took the same set of pictures, and Stewart, this perfectly built little Welsh guy, this little baby muscle monster, whom I’d known for years, was really impressed with the fact that I didn’t show genitalia and I didn’t show full frontal nudity,” Laurito said. “That was my own subconscious mind, I think, from all that Catholic upbringing: you don’t do that.”

Wherever it came from, Laurito’s reluctance to show dick and his use of artful cropping to make his pictures what he calls “classic,” instead of pornographic or specifically erotic, became a trademark of his style. “We tend, as a species, to gravitate towards those things that arouse us, and it arouses me too, but the facial expressions that you’d see in his eyes when he was talking were phenomenal. They were so sexy and so cool. When we were talking I said, ‘I would like to shoot you,’ and he said, ‘I’m not model material.’ He said, ‘You really are. You’d be surprised.’”

Stewart, with his pride in Laurito’s pictures of him, proved to be a valuable contact. Stewart was close to the people running Positive Nation, a British magazine for HIV-positive people similar to POZ or Art & Understanding here, and the man he worked for was a close friend of Mark, the man in charge of the British branch of Gay.com. “Mark said he wanted to start up exhibitions and give photographers the chance to express themselves on line,” Laurito recalled. “He said, ‘Send me a bunch of pictures. Let me see what you can do.’”

At the time Laurito was beginning his explorations with the Adobe Photoshop software — a tool that has since become so ubiquitous that its name has entered the language and “to photoshop” has become a verb — which he used, he said, to “put models in scenes and doctor the scenes up to give a kind of science-fiction type look to it.” Laurito had begun doing this for the greeting cards, and when he showed these to Mark, Mark used them in the on-line exhibitions.

In Control

From his earliest days as a photographer of people, Laurito made it clear to his models who was boss. He recalled he’d done that even before he became a professional photographer, when he was producing recording sessions. “When I wanted to get a rough sound out of their voice, it would really piss them off,” he recalled. “Then I’d say, ‘Let’s do a take,’ and I’d get the rough voice. They’d be pissed off, and I’d say, ‘No, fuck it,’ because it was important. I wanted to get that take, and they’d know exactly what I was doing.”

Laurito’s favorite photographer, the late Herb Ritts, would act similarly when he shot his famous album cover photos for Madonna. The first time they met, Laurito said, “she started doing the Madonna thing with him, and he got up and walked away. She said, ‘But that was a good one!’ He said, ‘You know what you’re doing. You don’t need me here.’ And he stopped. She said, ‘Fry an egg. Go ahead.’ He said, ‘Are you sure?’ She said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘I heard the arrogance in your voice.’ She said, ‘There’s always going to be arrogance in your voice.’ He said, ‘Good, because that’s what I want to hear. I wanted you, not somebody else.’ From then on they were best friends.”

That’s the message Laurito sends to his own photographic clients: if they’re paying him for his talent and expertise, he, not they, is going to control the session and decide what will make them look good. “I’ve turned down a lot of clients for personal photography, because if they’re coming to me they’re coming for my viewpoint, my perception of how to shoot them,” Laurito explained. “I tell them if they want their own viewpoint, they can take their own pictures. They don’t need me to take their pictures. They don’t need to waste their money on me. And usually I’m right. I’m always right in that respect.”

Laurito recalls being amused whenever he’s been on a shoot with another photographer taking pictures of the same subject but from different viewpoints and angles. “A really good friend of mine got me a photo shoot for Calvin Klein in the U.K.,” he said. “I usually don’t use anybody that muscular as the model. Short guy, too, and so beautifully built he scared me. You’ve heard of an ‘eight-pack’? He was a ten-pack! And the nicest guy.”

In this case, the other photographer working the session was Joanne, the model’s agent and also his wife. She casually asked Laurito if she, a professional photographer, could shoot during his session. “There must have been this look in my face like, ‘I’m going to kill somebody,’” Laurito recalled. “She said, ‘I won’t bite. I’ll sit behind you. I want to see if you shoot at the same times I shoot, and what we both shoot.’ Joanne went through three or four rolls of film; I went through about 10, because I was taking four shots for every pose, and it astounded me that when I was zooming out, she was zooming in. We’d be in the same general vicinity, and we had basically the same general idea, but we’d get a whole different angle to each picture. This was the first time it really dawned on me that two people taking the exact same thing can see it in totally opposite ways.”

Breaking the No-Nude Rule

Laurito said that one reason he generally avoids full frontal nudity and obviously sexual poses was that he wants his pictures to have an air of ambiguity — “like the Mona Lisa, where you see that smile and wonder, ‘What is she thinking?’” he explained. “I really try to create pictures that make people looking at them think, ‘What’s going on here?’ It’s neat, because 99 percent of the time I think I’ve got that. It’s usually trying to pull that thing out of a person that they’re hiding, that little secret side that they don’t want to show. The Indians say that a camera pulls out your soul, and it’s true. If you’re the right person taking the picture, you can pull out that side of a person that they’d never actually be willing to show.”

According to Laurito, he’s “actually become good friends with, I’d say, 90 percent of my models, which is a really nice feeling to know that you haven’t pissed them off in the process of photographing them.” He talked about two men who regularly sit for him every six months or so. “They’re typically very buff, bearish, manly, rugged, fuckin’-A type guys,” he said. “But the pictures they come out with in the sessions are very gentle. It’s the side of them that I know. It’s not the side that I see them with when I run into them in public, but when I’m in the studio with them I see the insecure and gentle people they really are.”

Photography, said Laurito, is “the kind of business where when you’re working with people, you can insult somebody really easily by not using something from the session, or especially when I won’t show things. I do a lot of shadowing, and some guys are very proud of their private parts and they want to show that. I explain to them, ‘It’s not what I take.’ But somebody else takes pictures of that, and they show it.”

Laurito recalled one model, Daniel, with whom he broke his no-full-frontal and no-dick rules. “The main reason I did that was because when I cropped it, it didn’t look like shit,” he said. “So I left it all in there. In the color version I cropped it, you didn’t see it, and it fit. But for the black-and-white version I needed a wide-angle lens because he’s a very tall guy and he had that long, kind of forlorn, look on his face.” When he couldn’t get the picture to look the way he wanted it to with his usual just-below-the-waist crop, he left Daniel’s cock in place, printed the photo and sent it to his agent, who forwarded it to Daniel.

Three weeks later, Laurito said, he got a phone call from Daniel’s wife Ann. “She said, in this wonderful British accent, ‘I just noticed he’s nude!’” Laurito recalled. “I said, ‘Ann, you gave me the best compliment you possibly could have. You’d hung the picture for three weeks and never noticed the guy was actually nude.’ She said it never even dawned on her. She was looking at the picture, not at his body. I came away from Ann with the best feeling that I’d ever had, that I’d accomplished what I really wanted to accomplish.”

Laurito’s less-is-more approach attracted business from a client whose aesthetic would seem as far away from his as one could imagine: a pornography producer. “They wanted to have what they considered classical pictures of their porn stars for the covers of their DVD’s, rather than the porn shots with X’s and all that,” he recalled. “They wanted something that would pull people in, so they asked me to do the cover shots for them. It was a session with a series of trolls. I couldn’t do anything with these people. They’re not cover material. They’re not going to pull in the public.”

The session was saved from disaster only when, as Laurito remembered, “a couple of them started coming back towards the end. They started realizing what I was getting at, that you can pull people in without showing the whole thing.” That’s one reason why Laurito rarely uses professional models, especially Gay men: because they’re too used to posing a certain way and it’s too difficult for him to shake them loose from their preconceptions of what makes them look good. “The message that I basically want to get through is you don’t have to make a nude body pornographic,” Laurito said. “You can leave it beautiful, leave it the way it is, crop a portion of the face and that’s perfect.”

Art in a Bathhouse

One of the unlikeliest places Laurito has exhibited is inside the Club San Diego bathhouse in Hillcrest. “I’m not really sure” how he got the invitation to hang his work there, he admitted. He thought it came from Jason, a manager at the bathhouse who’d seen Laurito’s exhibit at David’s Coffeehouse a block away from Club San Diego. “He came to me one day when I was in the club and said, ‘I want to spruce things up in here. We’re going to be repainting in here, and I could use some art on the walls, real art, rather than posters and such,’” Laurito recalled. “’If you have anything left over from any of your exhibits, please bring it over.’”

Initially Laurito saw the idea of hanging his photos in a bathhouse more as business promotion than anything else. “I always like hundreds of prints floating around to be seen by people interested in investing money in art,” he explained. But after a while he started seeing it not only as a commercial platform but an aesthetic one as well. Club San Diego’s owner rigged up some frames originally used for advertisements, which Laurito’s pictures could easily be slid in and out of to rotate the exhibits. Laurito returned to the bathhouse and, without revealing he was the photographer, started asking some of the people using the bathhouse what they thought of the pictures.

“One guy said, ‘It’s about damned time we started seeing some good stuff here,’” Laurito recalled. “’If I’m going to be walking around bored, I can look at something rather than a bunch of naked men.’ That’s exactly what the people running the bathhouse wanted. Jason wanted something on each wall between each room, so they painted the walls more often and it looks really cool.” In September Laurito took his camera into the bathhouse to take pictures of his pictures, and boasted that “it doesn’t look like a bathhouse. It looks like a high-class hotel. You’ve got real art on the walls, the painting looks nice and everything looks classy.”

Landscapes and Abstracts

Not all Laurito’s work involves the male form, even cropped, shadowed and made “classic.” He’s also an accomplished landscape photographer — something you have to be in the greeting-card business, he explained, where among the major demands of his clients is for stark, artful, shadowy pictures of trees. Laurito recalled one year he was shooting the annual benefit for the Servicemembers’ Legal Defense Network on the deck of the U.S.S. Midway (an abandoned aircraft carrier turned naval museum and party venue on the Embarcadero downtown) and, because it was too dark to get good pictures of the people at the benefit, he started shooting the scenery.

“Every year I get the most phenomenal pictures of the sunset,” Laurito recalled. “I’ve got one of a seagull sitting on a jet, and made it look like the jet is flying.” Jason of Club San Diego invited him to exhibit some of his landscapes at the bathhouse, “and I’m glad I have because it stimulates people’s brains. One guy said a picture of a tree reminded him of Death Valley.”

Laurito has also taken a series of particularly striking photos that are totally abstract, repetitive patterns inspired by the disciplined paper-folding technique the Japanese call origami. According to Laurito, the abstracts “developed themselves” out of his reliance on the image-manipulation technology of Adobe Photoshop. “Very rarely will I take a perfect picture,” Laurito admitted. “I’ll be tweaking it with color or contrast or brightness or whatever.” Soon Laurito became especially adept at using the “filters” in Photoshop, which are ways to distort a photo so it looks hand-painted or solarized, and also the “duplication” feature, which allows you to reproduce the same image again and again in a single frame.

“I would take a hillside, chop it in half, duplicate it, put it back together seamlessly, and create a myriad amount of phenomenal effects,” Laurito said. “Things came out of the images, like faces or whatever, which is kind of spooky when you look it it. It’s like, ‘Whoa! Is there something in there that I didn’t see?” His raw material for these images were the photos he took pretty much at random whenever he was finished with a project and was dealing with the post-deadline boredom and burnout.

Then he experimented with doing the duplication effect on the origami patterns a friend of his was folding. “I’ll take pictures of whatever he’s made and then crop it in half and dupe it, so I’ll have two halves of the same side,” Laurito explained. “I’ll put them together seamlessly and see what effect that produces. I might do that 15 to 20 different times and create a bigger picture in general. I’ve started with a small one, and it’s expanded from there. When you look at it overall, it’s scary what actually comes out.” But he doesn’t stop there; Laurito will then use some of the other controls in Photoshop, including a “metalflake” filter that “makes the edges look metallic,” to add even more “amazing” effects to the pictures.

Originally Laurito created the abstracts for his own amusement, “because to me it was just experimental,” he said. “It’s not photography; it’s just playing with it.” But one day he fished them out of the drawer where he’d stashed them, “and when I looked at them I said, ‘Jesus Christ! That’s beautiful!’” After a friend urged him to release the images and exhibit them publicly, “I talked to my agent and showed them to him. He said, ‘They’re tremendous! What are you going to do with all this stuff?’ I told him I’d either erased or thrown them away, and he said the best things people have done are usually the ones they’ve thrown away. It’s the ones you don’t think are good that other people like.”

The reception Laurito’s abstracts have received from people who’ve seen them in exhibits inspires a rare degree of philosophizing from him. “I’ve made them, but I don’t look at them as if I’ve made them,” he said. “I’m very objective with what I do. I look at it as if somebody else had done it. I’m proud of it, but I’m also critical of it. If there’s something that’s the most minutely wrong, I’ll toss it. I won’t use it. It bothers me. It makes me crazy. I’ll try to fix it if I can, but I’ve noticed that it starts to pull people in. They look at it, their brain is saying, ‘What’s this?,’ and their brain is interpreting it in its own way.”

That, said Laurito, is the effect he wants all his work to have on the viewer. “I’m supposed to make you think, to make you look at things not so much objectively but almost subjectively,” he explained. “You’re trying to make a determination, not so much of what the artist was saying — most people say, ‘I want to see what the artist was saying,’ but I don’t believe that’s true — but of what you think of it. Because you know what the artist is saying. He said it. It’s right there. I want to learn what other people are seeing in my pictures.”

David Laurito may be contacted by phone at (949) 510-5664 or via his Web site, www.laurito.com. He will donate a portion of the purchase price of any work bought at the Pleasures & Treasures show to the Elton John AIDS Foundation and local AIDS service organizations.