Wet: Adams and MOXIE Do It Again

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

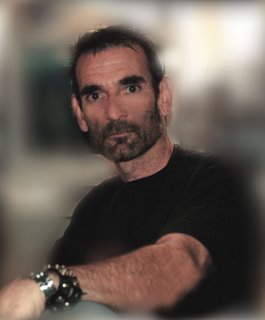

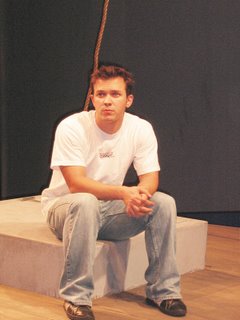

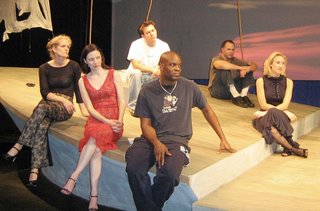

Photos, top to bottom: Chris Walsh as Jack the cabin boy; the cast of WET (L to R: Liv Kellgren, Jo Anne Glover, Chris Walsh, Laurence Brown, Don Loper and Jennifer Eve Thorn); WET playright Liz Duffy Adams and director Delicia Turner Sonnenberg

MOXIE Theatre’s latest production, a world premiere play by Dog Act author Liz Duffy Adams rather awkwardly called Wet: Or, Isabella the Pirate Queen Enters the Horse Latitudes, begins with a raging storm that sinks Isabella’s ship and claims the lives of all but four of her crew: Isabella herself (Jo Anne Glover), the gutsy take-no-prisoners pirate captain; Jenny (Liv Kellgren), her even more bloodthirsty (and butch) enforcer; Sally (Jennifer Eve Thorn), whose body is electrically charged from having been struck by lightning in a previous storm; and Viscountess Marlene (Don Loper), a male-to-female Transgender with fantasies of nobility. In a scene Adams admitted was inspired by the opening of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, the four unlikely pirates stand in front of a drawn curtain and hurl their hopes and fears at the audience in high-energy dialogue reflecting Adams’ skill at evoking the timbre of Shakespearean language without sounding like an undergraduate’s bad parody.

The opening sends a clear signal of what sort of show we can expect: one which will play with both high-culture and mass-culture symbolism, upsetting the audience’s expectations of gender and sexuality. Even people who come to the play with an acceptance of Queer sexuality and an openness to the possibility that not all the characters are going to be paired with partners of the other gender are going to be thrown by a few of Adams’ curveballs. After the anxious monologues at the start, the curtain rises on a damaged but still seaworthy ship, a naval vessel which likewise got caught in the storm and whose authoritarian captain, Joppa (Tom Deák), has likewise lost all but two of his crew: cabin boy Jack (Chris Walsh), who clearly has a crush on him despite his solemn warnings that sodomy is “a hanging offense,” and Horatio (Laurence Brown), a Black former slave who’s still feeling out how much of a difference his supposed “freedom” can make and how far he can push the rules.

Adams’ script for Wet, though not as strong as Dog Act — the exposition is clunkier and it takes longer for it to settle into a groove — provides a field day for a company interested not only in defying the stereotypes of what women can be and play on stage (MOXIE’s stated mission) but in exploring all sorts of dramatic and philosophical conflicts. The play pits straight against Queer, Black against white, male against female, authority against anarchism, war against peace and prescribed hierarchies against freedom. Its ideal is the fantasy island Isabella was hoping to find and settle — sailor’s legend or reality? Adams’ script leaves that question powerfully unanswered — where, tired of the life of a pirate and finding outlawry less free than she thought it would be, Isabella and her hand-picked crew hoped to set up a commune that would fulfill the anarchist ideal of “free association” and create a society that could function without coercion.

In the meantime, the seven motley sailors from two crews with two very different missions have to function together, and as the power shifts from one faction to the other, characters change sides and undergo wrenching emotional changes that leave them confused and disoriented. One of Adams’ strengths as a playwright is being able to write characters who are intensely theatrical, so obviously constructed to the needs of her dramatic design that you can’t imagine anyone like them existing in real life — while still involving us in their lives and emotions and getting us to care about them as if they were real people. As Jennifer Eve Thorn put it, “The characters are so intensely who they are, you can’t have any fear of being over the top. You have to abandon any thought of realism and just let yourself be this huge character every step of the way. I had so much fun with both plays (Dog Act and Wet), and now I can see people in the real world and say, ‘Oh, she’s a Jenny, all right.’”

Adams’ decision to make the play about pirates and set it in the past — typically, she says it takes place “many, many years ago” rather than limiting herself by specifying an actual period — gives her a rich mythology to fall back on. Adventure stories about pirates have been a stock-in-trade of popular fiction since the real-life prototypes of the characters in Wet were actually trawling the seas for booty-laden ships — and their continuing popularity is shown by the fact that both Pirates of the Caribbean movies, starring Johnny Depp, went to number one at the box office their first week in release. However the pirates may have really lived and worked, the popular imagination about them as it’s been expressed in books, plays and movies galore gives Adams a rich vein of pop-culture mythology to mine — and she brings in a mother lode.

MOXIE’s production and casting are all Adams could have asked for. MOXIE’s four plucky co-founders are all involved here: Glover, Kellgren and Thorn on stage and Delicia Turner Sonnenberg directing. Turner Sonnenberg’s direction ably captures the shifting moods and power relationships between the characters, and gets evocative performances from MOXIE and non-MOXIE cast members alike. Thorn’s performance as Sally is especially commendable. Playing a character whom Adams literally electrified to avoid the cliché of the highly sexual woman with a mental illness, Sally’s wrenching “human compass” routines (Isabella presses her into service to determine which way north is, and every time she does that it takes an awful toll and causes her to faint) and her anxiety over being untouchable — she still mourns for the boyfriend she accidentally electrocuted when he tried to kiss her — give Thorn plenty to work with. Glover’s Isabella — a role she said was challenging because she had to come from “a place of living in total arrogance” — is compelling in full pirate-queen mode and even more so when her guard comes down and we see hints of her softer side. Kellgren, playing the most one-dimensional of the woman-born women in the script, still finds depth and shows us the pain underlying the character’s violence and rage.

Of the male performers, Laurence Brown stands out, particularly if you saw him in the title role of 6th @ Penn’s compelling adaptation of Sophocles’ Ajax. The two parts couldn’t be more different — Ajax an intensely physical expression of machismo become madness; Horatio a self-described philosopher who, having known both slavery and freedom, ponders the difference between the two and wonders whether it’s as great as had been advertised — and it’s a tribute to Brown’s rangy acting skills that he is equally convincing in both. Walsh’s Jack is especially strong in his expression of hurt pride — at one point Adams has Jack bitterly resent still being called a “cabin boy” when he’s biologically a man — and his goop-eyed admiration for the captain, though he overdoes the latter enough that almost from his first appearance one wants to whisper in his ear, “Kiss him, you fool.” Deák, playing the closest thing this play has to a villain — Adams’ jaundiced view of current events comes through loud and clear when he says he needs to get his ship back to port so it can be repaired and he can return to the war, and Marlene says, “There’ll always be a war somewhere!” — manages, despite having Adams’ most weakly written role, to be convincing as an authority figure and to soften when the script gives him the chance.

MOXIE’s physical production also does justice to Adams’ compelling play. Eric Lotze’s lighting and Rachel Le Vine’s sound vividly bring Adams’ Tempest-tossed opening to life. The set by Jerry Sonnenberg (director Delicia Turner Sonnenberg’s husband) is remarkably elaborate and solid, looking genuinely like a ship and not a pile of pallets or a raised disc. Like Dog Act and most of MOXIE’s productions, music and song figure prominently — the second act features two concerted vocal numbers, both with lyrics by Adams and music by Cliff Caruthers, and the final song, “Wet,” actually ties the plot together and brings about the resolution — and vocal coach Steve Gunderson works magic with the nonprofessional voices. The costumes by Fred Kinney and Amy Chini are appropriate to the audience’s expectations of how sailors and pirates would dress, and though fight choreographer Tim Griffin has less to do here than he did in Dog Act, he does it convincingly.

Adams admits that it took her an unusually long time to write Wet. She began it in 2001, just before the 9/11 attacks, and only recently finished it. (Indeed, MOXIE meant to use it as the opening production of last year’s season and did Dog Act instead because Wet wasn’t ready.) “While I was working on it, it was operating on two different levels,” she explained. “One was thinking deliberately about the immediate post-9/11 era and the buildup to war. At the same time, I was thinking more broadly, more philosophically, about hat is the moral way to live in the world right now.” The result was a play that works as a political allegory but doesn’t turn preachy or wear its heart too blatantly on its sleeve. MOXIE’s production is fully alive to the strengths of Adams’ script and covers for its occasional clunkiness. Wet is a theatre experience not to be missed.

Wet: Or, Isabella the Pirate Queen Enters the Horse Latitudes plays through Sunday, December 10 at the Lyceum Space, 79 Horton Plaza at Fourth and Broadway downtown. Performances are at 8 p.m. Thursday, Friday and Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $20 Friday through Sunday, $15 on Thursday. Discounts: $15 for seniors, $10 for students. For reservations or other information, please call (619) 544-1000 or visit www.moxietheatre.com