The Pride Beatings

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

On Saturday, July 30, shortly before the San Diego Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Pride Festival closed for the night at 11 p.m., at least five people leaving the festival were attacked with baseball bats. One of them was also stabbed. But this isn’t an article about the beatings themselves, but about how the city government, the police department and the Queer community itself responded to them.

On the surface, the response was just fine. Mayor Jerry Sanders, formerly San Diego’s most Queer-friendly chief of police ever, sounded like he was still a police chief when he gave a press conference the next day and said, “I have a few choice words for the criminals who committed this vicious attack — and for any others who are contemplating perpetrating such a crime: You’re cowards! Make no mistake about it: if you commit such a crime, we will do everything within our power to catch you.” Within three days of the attack, three suspects were in custody — a far better performance than the city gave the last time the Pride events were attacked, when a tear gas canister was thrown into the reviewing stand at the parade in 2000 and, despite two years of assurances by then-police chief “Cowboy” Dave Bejarano that they were on the point of solving the crime, no one was ever arrested or charged.

But Zenger’s associate editor Leo Laurence heard a different story from one of the victims, 34-year-old Paul Mullins from Cincinnati, when he interviewed Mullins for an article in the August 13 San Diego Metro Weekly. Mullins told Laurence there were at least five assailants, and that when he used his cell phone to call 911 and inform the police that he and others had been attacked with baseball bats near the festival grounds, the 911 operator “didn’t know where I was.” The operator didn’t know the geography of Balboa Park or the exact location of the Pride Festival, and Mullins was on hold when he heard the sounds of more people being attacked.

“I heard someone yelling for help,” Mullins told Laurence. “I ran into another person. I don’t know who he was. ‘What are they doing? Are they beating up Gay people?’ the man asked.” Mullins said they were and told the man to get some of the Pride Festival’s own security people and the police officers assigned to the event — without success. The police officers were sent home at 10:30, just before the attacks occurred, and the uniformed guard who identified himself as the head of security for the festival told Mullins, “First of all, we don’t get paid enough to get involved like that and chase people.”

Judging from the pathetic response of the 911 operator — who kept Mullins on hold even as he was witnessing more victims being attacked and pleading with the operator to send some officers to the scene — and the lackadaisical attitudes of both the police and private security people on the scene, it’s clear that the attitude of the top city leaders that this is an event to be protected and nurtured hasn’t filtered down to the rank-and-file. Relations between the Queer community and the police have never quite recovered from the days in which sex between same-sex partners was illegal and the police regularly raided Gay bars, arrested patrons, released their names to the media and frequently provoked them to suicide.

As police chief, Jerry Sanders was a leader in doing outreach and education programs for his officers and training them to be sensitive to the Queer community. But programs like this can only go so far in erasing long-standing homophobic prejudices among many police officers. There are still too many stories of Queer crime victims reporting assaults, robberies and the like to the police and being patronized, disrespected and sometimes even threatened with arrest themselves.

What’s more, as noble as the statements by city leaders and the speed with which at least some of the assailants were arrested may appear on the surface, there are also elements of damage control. Mayor Sanders may be a decent man and as Queer-friendly as we could hope for in a man of his position and background, but he was also motivated by the fact that — as he stressed in his public statements of support for the Pride events before they occurred — the events bring in $21 million annually to San Diego, most of it from out-of-towners like Paul Mullins. Especially in a city as economically dependent on tourism as San Diego, Sanders and the city government don’t want to jeopardize that windfall by letting the word get out that it’s unsafe to attend San Diego Pride. Also, Laurence told Zenger’s he did the interview with Mullins just an hour before all the victims received calls from city officials telling them not to talk to the media — a pretty persuasive hint that the city has something to hide.

The Queer community is also in damage-control mode. At least two weeks before Pride, “Papa” Tony Lindsey of the San Diego League of Gentlemen was sending e-mails alerting the people on his address list to a wave of hate crimes in Hillcrest. The local Queer media (including this one, I’m ashamed to say) ignored his warnings. That in and of itself should have made people aware that there was a good chance for a Queer-bashing attack on Pride and that this was not a year for “business as usual” with disinterested security people and clock-watching police. Since Pride other attacks have been reported on Queer individuals and businesses in North Park and even Linda Vista — and they’ve been reported, if at all, as individual events despite the fact that the suspects arrested in the Pride attacks were all members of a gang called the “Lowlifes.” To me that suggests a strong possibility that the attacks are part of a coordinated criminal assault on our community and its people — but no one’s talking about that because it would be bad for business.

In 1991, when John Robert Wear was killed on the streets of Hillcrest near the Obelisk Bookstore, the community organized. It held meetings at Rich’s and formed a Citizens’ Patrol of community volunteers to drive through the streets of Hillcrest and North Park and alert the police immediately at any sign of potential danger. Fifteen years later, the community leadership is staging meaningless feel-good rallies in front of the Center instead of actively organizing for self-defense. Is it going to have to take another murder to goad us into acting to protect ourselves?

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

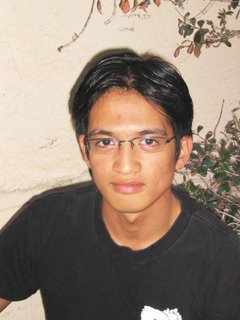

REDENTOR “RED” GALURA:

UCSD Student Comes to Terms with His Bisexuality

interview by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

Redentor “Red” Galura is a slim, dark-haired, outgoing, energetic UCSD student who knew there was something different about his sexual orientation even before his family moved here from his native Philippines when he was 15. “I always knew I wasn’t straight, but I couldn’t quite put what it was, because back in the Philippines we didn’t have a term for bisexuality,” Galura said. “It was just you’re either Gay, Lesbian or straight.”

Despite the ostentatious project over the last decade or so of renaming the Queer community itself and virtually every organization in it with the unlovely acronym “LGBT” — for “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender” — all too many Queer folk still divide humanity into “Gay, Lesbian or straight.” Too often Bisexual people like Galura are still called “fence-sitters” and even nastier epithets by people who’ve worked their way into an exclusively homosexual identity and have a veiled — and sometimes not-so-veiled — contempt for those who can’t or won’t restrict their sexual interests, attractions, desires and acts to only one gender.

In addition to majoring in physiology and neuroscience at UCSD and pursuing a career goal to work with animals, Galura is also heavily involved with the UCSD LGBT Resource Center, where he will be one of eight student interns this school year. Zenger’s caught up with him one August afternoon after a summer-school midterm and he discussed his experiences as a student, a Resource Center volunteer and a budding Bisexual with a desire to find a nice boy or girl and settle down.

Zenger’s: I just wanted to get some of your background and how you came to an awareness of your own sexuality.

Redentor “Red” Galura: I’m a student at UCSD, going into my third year. Before that, I originally came here from the Philippines when I was 15 years old and lived in Daly City, which is right next to San Francisco. Growing up, I always knew I wasn’t straight, but I couldn’t quite put what it was, because back in the Philippines we didn’t have a term for bisexuality. It was just you’re either Gay, Lesbian or straight. So when I had these attractions to males and females, I was very confused. When I came to UCSD and visited their LGBT Resource Center, I found out about the LGBT community and put a term onto what I was.

Zenger’s: What’s your involvement with the LGBT Resource Center?

Galura: For the past year I was just involved in all the various clubs and student-run organizations that we have. I was a newbie to the community, so I came to the Resource Center to learn about all the other stuff I could get involved with, LGBT-wise. They gave me a list of all the orgs. I joined a bunch of them and found which ones I liked and which ones I didn’t, and stuck with the ones I liked.

At our Resource Center we have so-called student interns, and there’s about eight of them. I applied for one of the internships, and so for school year 2006-2007 I’m going to be the Speakers’ Bureau intern. Basically what we do is gather a few LGBT-identified students on campus, and basically we come into classes or RA’s, residential advisors’ events for their dorms or whatnot, and just speak about our lives, our experiences. We hope that through that we raise awareness and acceptance in the community.

Zenger’s: Could you tell me a little about the new facility at UCSD?

Galura: I like it. Compared to our old Resource Center, it’s a mansion, about six times as big as the last one. From what I hear, it’s the largest LGBT resource center in a public institution of higher education. Our Resource Center is a really important facility for everyone on our campus, LGBT-wise. It’s a place for us to hang out between classes or just relax. It gives a safe and secure environment for LGBT-identified students to just come and be themselves; for student orgs to meet. It’s especially important for our coming-out groups, male and female alike, as like I said, it provides this really safe and secure space where hopefully they feel welcome enough to come in so we can help them out.

I remember the grand opening. It was early, on a Saturday morning, and it was at the very end of what we call at UCSD our “Out and Proud Week,” a full week where we dedicate ourselves to being visible. I remember the chancellor was there, and various LGBT-identified faculty and staff were there, some of whom I’d never met before. It was quite surprising to see that many, because I’d never seen them at the Resource Center before. Students were there. It was just a great time. I guess. Everyone was waiting for the new one to open up since the old one was closed for a while and there wasn’t really any space to go to, so I guess, yeah, that showed how important it was to us, I guess.

Zenger’s: How do UCSD’s non-LGBT-identified students react to all of this?

Galura: I remember there was an article in the Guardian, which is the UCSD student paper. I remember at first there was just a picture, and I was actually in the picture on the front page of the paper. A week after that, my roommate wrote an article for the Guardian on the grand opening, so everybody heard about it. I haven’t really heard direct reactions to the new LGBT Resource Center opening. Nothing negative or positive from my non-LGBT-identified friends or whatnot.

Zenger’s: I was thinking of the horror stories that I’ve heard from the students at San Diego State, where they had their rainbow flag stolen. At their LGBT Visibility Week they’ve been hassled and confronted. I was wondering if anything like that was happening on UCSD as well.

Galura: At our Resource Center we have this historical binder that I read over. I don’t exactly remember the details, but occurrences of harassment have occurred in the past, but not lately. I haven’t really heard any outright or blatant attacks on LGBT students whatsoever, so I would guess the UCSD campus is relatively pretty open.

During the school year I had my own rainbow flag out in the balcony of our apartment. When I was first thinking about putting it up there I talked to my straight apartment-mates first because I guess I was just being pessimistic about hate crimes and such. I was just being careful, not wanting them to be affected by my decision to be out and proud. But they were fine with it, and my flag was never taken down or ripped off. Our apartment was never egged, or anything like that.

I lived in the single room, which is right next to the main walk that sees our balcony, and I never heard any negative remarks about the flag. Although Once there was this lady who came to our apartment to talk to me, because she saw the flag and apparently she thought, since I had that flag, that would be supportive of this project she had to try to get President Bush out of office. I don’t know why. But that’s the only reaction I’ve got to it so far.

Zenger’s: How did you decide to identify as Bisexual rather than Gay?

Galura: That was during the last two years of high school, I guess. I always knew I liked guys, but I liked girls as well. I couldn’t really explain why that was until I moved here and learned about the term. I came out to myself in the senior year of high school, but didn’t really come out to anyone until towards the end of my senior year in high school. Ironically enough, I came out to a girl I had a crush on back then, and she was fine with it.

Zenger’s: How did you come out to your parents, and how did they respond?

Galura: I came out to my parents last Thanksgiving, 2005. It was really scary at first. I was sort of expecting that if I came out as Bisexual, my parents would ask me, “Why don’t you just choose girls over guys, then?” or something like that. My parents were really religious, Catholic, and that’s how I was brought up, so I was sort of expecting that reaction from them. But it turned out that was very wrong.

I sat my parents down at the table a few hours before I drove back down to San Diego, and I told them, “Mom, dad, I’m Bisexual.” There was just silence at first, and then my mom turned to my dad and asked him what “Bisexual” meant. There was a little chuckle from both of them, and then my dad explained what Bisexual meant to my mom, and she just ent, “O.K.” Then my dad turned to me and asked me why I came out to them. Was it because I needed help, or because I just needed them to know? I told them it was just for their own information. He was fine with it, and he just started asking me about other stuff.

I told a Gay friend of mine about it on the drive back to San Diego. He told me his own experience, where at first his parents were very open to it, but then in the following months they just started acting weird. He told me to give it six months, to see how they reacted long-term. They haven’t really changed their views or treated me any differently. I think we’re even closer now, because I can openly tell them about my involvement at the Resource Center and all the other extracurricular stuff I do besides school — and I can tell them about my crushes.

Zenger’s: How have the other people at the Resource Center responded to you? Have they been supportive? Have you gotten any of the “fence-sitter” epithets?

Galura: The majority of the community has been very supportive, because we do have a number of Bisexual students as well. I’ve only experienced these stigmas from one Gay student. I remember it was at our “Non-Sexist Dance,” where it’s not supposed to matter what sex you dance with. and his partner noticed that for the whole night I was mostly dancing with girls. At the end of the night he asked me why was that, and I told them it just happened that way. I wasn’t really looking for anyone or anything that night. I just wanted to have fun.

Then his partner asked me, “You identify as Bisexual, right?” I said yes, and the partner said, “Oh, Red, don’t play that card with me.” I asked him, “What card?” He said, “Oh, you know. I had a friend back in Ventura who identified as Bi at first, but then he was only attracted to guys. He was one of those ‘Bi now, Gay later’ people.” That really hurt, especially coming from someone I thought was a friend. It felt like he was making me deny a part of me that was attracted to girls, but what am I supposed to do with that? It is there, and it’s not going to go away.

Zenger’s: If you had a chance to have a rational conversation with that person, what would you want to say to him?

Galura: He was really drunk at the time, so I just sort of dismissed it, but it didn’t hurt any less. But if I were to talk to him again, I’d tell him I actually believe that everyone’s inherently Bisexual to some degree. Some people are more towards heterosexual attractions and some people are more towards same-sex attractions, but I think everyone has that capability to be Bisexual. What I’ve learned from our Resource Center is that your sexual attractions now aren’t necessarily going to stay the same as you grow up. They might be the same, but sometimes they will change, and that they will change again. Sexuality is just very fluid that way.

Zenger’s: It’s occurred to me that if we could break down all the homophobia, all the anti-Queer prejudices, we probably wouldn’t have that many more Gay or Lesbian people, but we’d have a lot more Bi people.

Galura: That’s what I think, too.

Zenger’s: Based on people you’ve known and talked to, do you think that women accept bisexuality more readily than men do, especially the potential of their own bisexuality?

Galura: I would say for the time being that’s true. Right now in our society, our American culture, one of a straight guy’s fantasies is to see two women going at it. You see that represented in commercials, in movies, especially in porn. I don’t really know why. I guess it’s just part of that whole homophobia, where it’s O.K. for women to do that but for males, you always have to keep this front of being masculine and strong. Stereotypically speaking, Gay men are seen as feminine or whatnot, and when even like just one same-sex encounter happens, a man will see that as a sign of their masculinity being less or something like that. Unfortunately, our society is still very patriarchal, and any sign of weakness in a male is seen as bad.

Zenger’s: That’s what the late Albert Bell was getting at when he said, “Homophobia is misplaced sexism” — that a society that looks down on women, and looks down even more on men who “take the role of women” by being Gay, by having sex with men.

Galura: That’s interesting, because last week I sat in at one of the psychology classes on human sexuality, and the topic was on sexual orientation. One of the things the professor said was that the struggle LGBT rights is really tightly interconnected with other civil rights movements, especially issues of gender. She said that sexuality and gender are intricately connected; our society has this idea of what’s “male” and what’s “female,” and it automatically assumes that if you’re not one, you’re the other, when that’s not necessarily true. I guess that translates to being straight and being Gay. If you’re a “man” you’re supposed to just like women, and the stereotype is that if you’re male and you like men, you must be a “woman.” It doesn’t really add up.

Zenger’s: Apropos of that comment that the struggle for LGBT rights is interconnected with other civil-rights struggles, one of the obstacles our community is running into is that a lot of people of color, who have gone through their civil rights movements, are also socially conservative and therefore come out as anti-Gay. People of color, for example, have been more likely than whites to vote against same-sex marriage when those initiatives come up, and we’ve had a lot of groups, for example the African-American churches, mobilizing very heavily to oppose Queer rights. I was wondering, as a person of color, do you find any of this in your own community, any social conservatism that gets in the way of their being able to accept LGBT folk and the idea that LGBT folk should have rights?

Galura: In the Filipino community, you mean? When I was growing up in the Philippines, relatively speaking it was pretty open. We had Gay celebrities and Gay TV hosts, and there’s not really that big an opposition against being Gay. But since it’s a primarily Catholic country it’s still looked down upon by some people. Hate crimes do still happen, though I guess not on a grander scale than here in the U.S. Same-sex couples still can’t marry back there.

At the UCSD Resource Center we actually have a group for Queer People of Color formed recently, around 2000 or 2001. We call it “Q-POC,” and it’s a place where our intersecting identities, whether it be our sexual orientation, ethnicity, nationality or religious affiliation, no matter what, we know that those identities might conflict with each other, but we try to intersect them anyway. It’s one of the more activist groups out of the ones at UCSD.

DAVID ROVICS: Political Singer to Play in San Diego September 8

interview by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

In the early years of the 20th century, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a combination labor union and revolutionary political organization, published a red-covered, pocket-sized songbook — mostly of radical political lyrics to traditional hymn tunes — which they called “Songs to Fan the Flames of Discontent.” America’s political folksingers have been fanning the flames of discontent ever since, from the IWW’s Joe Hill (convicted on trumped-up charges and executed in 1915) to Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger in the 1940’s, Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs in the 1960’s, Utah Phillips and Fred Small in the 1980’s, and now Roy Zimmerman, Dave Lippman, Charlie King, the Prince Myshkins — and David Rovics, who’ll be bringing his songs and stage raps to San Diego Friday, September 8, 7 p.m. at the Sherman Heights Community Center, 2258 Island Avenue.

Rovics has been active in political music since the early 1990’s and has played San Diego before in benefits for local independent media organizations. This time he’s coming on behalf of Activist San Diego and also to promote his new CD, Halliburton Boardroom Massacre, due out September 5. He’s released seven previous CD’s and one cassette, mostly on his own Ever Reviled Records label, and both his commercial releases and more than 200 free downloads (alternative versions of songs from his CD’s as well as some he hasn’t otherwise recorded) are available from his Web site, www.davidrovics.com

Zenger’s: How did you get interested in being a political folksinger?

David Rovics: I grew up in a musical family. My parents were both classical musicians, and so I’d been playing music since I was young. I got exposed to notions about all not being right with the world at a fairly early age, starting with the anti-nuclear movement when I was 12, right after Three Mile Island. I was going to this camp where there were anti-nuclear activists coming through, so that was kind of the beginnings of my political consciousness. It all came together for me when I first heard a whole bunch of musicians around the same time: Utah Phillips, Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Jim Page, Buffy Sainte-Marie. I liked this stuff, so this was what I wanted to be doing.

Zenger’s: What was the last name you mentioned just before Buffy Sainte-Marie?

Rovics: Jim Page, who’s actually the least-known and the best of all the songwriters that I would ever mention. He’s phenomenal. He’s from Seattle and he’s been at it since the late 1960’s, and never achieved a great degree of fame outside of Ireland.

Zenger’s: When did you start writing and performing songs yourself?

Rovics: I started writing when I was around 19 and go more serious about it in my early 20’s. Many people accuse me of being in-your-face and not very subtle now, but it was a lot less subtle then. I think it developed a bit of three-dimensionality from me after1993, when my friend Eric Mark was killed. We were down in the Mission District in San Francisco on May Day, hanging out with Maoists, which I used to do quite often, spray-painting buildings with revolutionary slogans. There was a gang war going on between two different Mexican gangs, that none of us were aware of, not actually being very proletarian. Maoist kids didn’t know what the proletariat was up to around there, really.

Members of one gang hit up Eric and another guy for money, and then for whatever random reason, after having their money, were going to shoot the guy Eric was with. Eric stepped in front of the gun, in between the gun and the other individual, and they blew his head off. I was three stories up in an abandoned building, not able to see what was going on in any detail. All I could see was the gunshot, and I knew somebody had been killed but I didn’t know who.

Zenger’s: The stereotype is a conservative is a liberal who gets mugged. Why didn’t the murder of your best friend swing your politics towards the Right?

Rovics: It swung my politics towards three dimensions, really. I think this happens to a lot of people, somehow or other. There’s definitely the liberal-that-gets-mugged phenomenon, that’s for sure. We’ve seen that many times. But there’s also the phenomenon that you have a certain degree of understanding reality, and then it sort of punches you in the face and you understand it a little better and a little more intimately, a little more personally. So that’s the effect it had for me.

I wasn’t stupid. I was an active young radical and I knew the social conditions that people in the Mission District were coming out of, in theory. I knew that the District was and is largely populated by refugees from Central America who are escaping horrible war zones. I knew about the ways our Army taught their soldiers how to torture, and how many torture survivors, dealing with horrible traumas, are in San Francisco living as refugees. I knew about all that, but to be suddenly confronted so intimately with that reality actually for me made the suffering of people around there just a little more personal.

Also, I’m not a liberal, right? From the viewpoint of people who would call themselves radicals of one form or another, the term “liberal” is an insult. To me, it refers to people who talk a sort of semi-radical line in order to confuse the public and get their votes. People like Hillary Clinton. Somehow or other a lot of people think she’s against the war, but she’s not. She’s actually completely supportive of Bush’s invasion, but people have this idea about her that has nothing to do with her actual politics.

So maybe the liberals who get mugged and then become fascists are the ones who didn’t have much of a grasp of reality in the first place: the ones Phil Ochs wrote about in “Love Me, I’m a Liberal,” the ones who like Black people as long as they don’t move next door, that sort of thing.

Zenger’s: In the early 1990’s, what issues were you singing about, and how does that differ from what you’re singing about now?

Rovics: The things that were catching my attention in the 1990’s were actually not that different from the things I’m concerned with now and writing about now. They tend to fall into three vague categories: the global justice movement, the anti-war movement and the environmental movement — all of which, of course, were happening then as they are now, and as they were five years ago, but in very different forms in all those different periods.

I was a big fan of Noam Chomsky and was really wondering why there weren’t more people in the streets confronting the World Bank and the IMF [International Monetary Fund] after reading so much about what they were doing, and how opposition to these institutions is potentially something that could unite people so much around the world, because they stand for everything that’s wrong with the sort of modern monopoly capitalism. I was so excited when finally in the United States in 1999 that global movement against these institutions for a more equitable, just economic division in the world started up in a big way in the streets of Seattle and elsewhere. But that’s something I’d already been writing about for a while.

Then there were the sanctions on Iraq. The anti-war movement, to the extent that it existed then — which was not much at all — was chiefly concerned with the sanctions on Iraq that were killing hundreds of thousands of people. So I was writing and thinking about that a lot, and about the deterioration of the environment, and global warming. That’s something I write about a lot: suburban development, sprawl, “Song for the Earth Liberation Front.”

Zenger’s: I noticed that on the compilation CD Behind the Barricades: The Best of David Rovics you had a number of what I might call “wise-guy songs” on that disc, like “Song for the Earth Liberation Front” and “Song for the Biotic Baking Brigade” [a group of anarchist vegans who threw pies at political and corporate leaders]. You don’t seem to be quite so much of a wise guy anymore. Have you really moved away from that kind of songwriting, and why?

Rovics: I guess I’ve moved away from it. I do a bit less of it, proportionately. I like songs like that, but their only real audience is the activist community. It’s fine to write songs for that audience, but I’m more interested in and more thinking about writing songs that have more of a potential for universal appeal and understanding, things that are more based out of things that people know about.

I’m also doing less of it as a reaction to the global justice movement in the U.S. pretty much collapsing after 9/11. Certainly it’s going strong elsewhere, but I’m mostly in the U.S. writing about stuff that’s happening in the U.S., and that movement is not doing the kind of inspiring things in the U.S. that it had been doing around 1999, 2000, which was inspiring more “Go get ’em, fight!” songs. After 9/11, it just seemed harder to write these kinds of flippant songs. The atmosphere in the country changed, really, so joking about some things just became less funny somehow.

Zenger’s: A number of your songs are about subjects and stories that most people have never heard of. For example, the song “St. Patrick’s Battalion” was about an event I had only read about in two sentences in a book about Mexican history. [They were a group of Irish-American soldiers in the U.S. army in the 1846-1848 war against Mexico that deserted and joined the Mexican side.] I had to ransack the memory tapes when I first heard that song to remember what that was about. How did you find out about the St. Patrick’s Battalion, and what moved you to write a song about it?

Rovics: It was in a lecture by Howard Zinn, author of the book A People’s History of the United States, and I think I read about it when I read that book many years ago. I thought, “Wow, what a neat story,” and I did a search on it on the Web. There were a number of Web sites dedicated to the memory of the San Patricios, and they’re quite well known on the Left in Mexico and among Republicans in Ireland. I thought it was just a great story, really right, just perfect ballad material for a song.

With a song like that you can just tell the story and people learn something new. There are a lot of basic archetypes involved: the notion of having so much dedication to a cause that you not only desert from your own army but join the opposing army, simply because they’re the ones being invaded — not even because you have some kind of a commitment to their country or to their government, which was at times really tyrannical, but just being willing to die for the lesser of two evils, when it comes down to it. It sends chills down my spine just to think about it.

Zenger’s: One other song that struck me about a more recent event, the “Spanish Journalists’ Strike.” I think of myself as well informed, and I hadn’t heard of that. [It was a protest against the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq, which then included Spain, deliberately targeting and killing journalists.]

Rovics: Yeah, that was another obscure event. I think it was headlines in Spain and other places, and it certainly made the news in the U.S., but if it made it into the New York Times it was probably somewhere at the very end of the World News section. But yeah, that was a neat little event; there’s something about the concept of people who are actually the news reporters not reporting the news.

Aznar [then the prime minister of Spain] was about to give his major national address, and just as he’s about to do this all the people with the cameras, all the people with the notebooks and pens, all the people with the microphones, just put them down on the floor and turned around and walked out of the building. I loved it. It was beautiful. And nobody was there. The entire room emptied out, and they all went over to the U.S. Embassy and had a protest, because of course the U.S. had just killed a number of journalists in one day, in different locations, fairly clearly on purpose.

Zenger’s: I’ve noticed that recently you’ve been writing quite a few songs about the Palestinians and the Israeli occupation. How did you get interested in the Palestinian situation, and what have you gone through to be able to turn that into material for songs?

Rovics: I first became aware of what the reality of Palestinian and Israeli history through reading Noam Chomsky when I was a teenager, but it became more of an intimate thing for me after I did a tour in Israel, organized by the Israeli Folk Music Society. I was kind of suspicious of them in the first place. I felt like I was doing a tour of apartheid South Africa and only playing for whites. I was already aware of the situation, but I thought I’d do it anyway, just to see what it was like.

I hadn’t written any songs about the Palestinian struggle at the time. I had written songs against the bombing of Iraq, but I hadn’t done anything about Palestine. So I was kind of undercover, in a way, and after my experiences there, especially with Israelis, I realized it is the most racist society I’ve ever come across. I’ve been in quite a few, but that really took the cake in terms of the way that people refer to Arabs — and of course the Palestinians don’t exist in the minds of the Israelis. They’re just “Arabs,” and the way that they talk about them just reminds me of the way the typical whites might have talked about Black people in Alabama in the 1960’s.

It was just the next year that [former Israeli prime minister Ariel] Sharon, the butcher of Shatila, on the anniversary of the massacre went to visit the al-Aqsa mosque that set off the second intifada. I was in Europe at the time, and unlike the American media, the European media you were seeing bloody images of children being gunned down by Israeli soldiers with machine guns. It always helps to have that really graphic kind of media coverage to start writing a decent song. Having the images there is not as good as being there, but having been there and having seen these images, I wrote a song about it called “Children of Jerusalem.”

That started the process, because suddenly I started hearing from lots of people who hate the song — and then, about a week later, lots of people who love the song wrote. It trickled out to different circles at different times, but it quickly got to both the Israel supporters and the Palestinian intifada supporters. Then I started meeting more people from the region, especially Palestinians, and hearing their stories about their lives, which are so powerful, horrific and very well told, and so intimately related to U.S. foreign policy and also so intimately related to my own family history.

My father is Jewish, and I grew up hearing about the Holocaust and hearing about how we shouldn’t treat people badly, and how supportive Jewish people of their generation were of the civil-rights movement in the U.S. and Israel. And to see what such an abomination [Israel’s policy towards the Palestinians is]. There were so many Palestine songs.

Zenger’s: Have you ever thought of doing a totally non-political album: Another Side of David Rovics, as it were?

Rovics: I have thought about it, but I don’t know when or if I’ll ever get around to it. I’d do it if somebody wanted me to. I’m only doing one CD a year, and I don’t know if I’ll ever make a non-political album enough of a priority to do a whole CD of love songs, but I have thought about it and I’d kind of like to do it. I agree with what Dick Scoggins says that they’re all love songs, and I’ve written a song to that effect as well. But I think at the same time there are songs that are really not political: songs about life and personal experiences.

I tend to like to combine them more. I think that’s a nice way to deal with it. But I’ve thought of doing a non-political album mainly because I don’t like the way I combine them. I much prefer the way Jim Page combines them. With him it’s more like two-thirds political, one-third non-political; and of the two-thirds that are political, many of them are more personal stories too. I think that kind of songwriting really does it for me. His body of work, the way it varies like that, is great. I wish I wrote more like that.

Zenger’s: Especially since I think it’s when you have written like that that you’ve done your best songs, like “The Key” on the Return CD or “Four Blank Slates” on the new album, where you can bring the issue home emotionally and show how it affects real people, how it tears people apart.

Rovics: Right, making it personal, making it relate to things that people can relate to, because just living on the planet, you know, songs like “Jenin” and “The Dying Firefighter,” songs that are about actual people in situations that are familiar, like in “Jenin,” a kid going to high school and just having all these things happen. People can relate to that because he’s a kid going to high school.

Zenger’s: I particularly liked the song “I’m a Better Anarchist” because we’ve had experience with those people just trying to top each other on all the different numbers of things they’ve been against. My partner had joked that you score brownie points in the anarchist community by the sheer number of things you can be against, and your song was basically the same joke, set to music.

Rovics: Absolutely. I love these young people and their dedication, but they are definitely worth teasing and they definitely need to maybe take life a little less seriously — not necessarily take life less seriously but take themselves a little less seriously. They think they have the last word on everything, and it’s typical teenage-type stuff, but it’s well worth teasing people about having that kind of attitude. It has a detrimental effect on groups that people are trying to work with. Too often people feel like they’re just stabbing each other in the back and feeling betrayed and bogged down in ridiculous little discussions about every detail of everything that’s happening. I can understand where they’re coming from, of course, but it’s got to be poked fun of. Plus I wrote another song teasing the Communists, called “Vanguard,” so I felt I had to have one to balance it out and tease the anarchists.

“Creating Chaos” Teach-In Explores Middle East Issues

Speakers Call on U.S. Peace Movement to Endorse Armed Resistance

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

Three powerful Arab-American speakers assembled at the Polish-American Association building in Golden Hill August 25 to give a different view of the current crisis in Lebanon and the overall status of the Middle East from the one usually heard in the mainstream media. But the presentations of Elias Rashmawi, national coordinator of the National Council of Arab-Americans; Grossmont College professor Basheer Idoui and local attorney Nadia Keilani, presented by the Middle East Cultural and Information Center (MECIC) under the title “Creating Chaos: Civil War 101: The U.S. Agenda in the Middle East,” traced the history back to 19th century colonizers from the major European powers and called on American peace activists to support armed resistance movements like Hezbollah and Hamas.

Idoui, the first speaker, called Israel’s recent attacks on Lebanon “the total destruction of an entire country through destroying its infrastructure and massacring its civilian population, of which Qana was just one example. At least 1,400 Lebanese have been killed, one-third to one-half of them children; 500,000 people displaced from their homes and Lebanon bombed back to the state it was in 15 years ago. It will take an estimated $15 billion to rebuild.” Idoui said Israel’s attack on Lebanon was “nothing new,” noting that in 1982 “there was also a systematic destruction of Lebanon [by Israel] in which 8,000 people were killed, Beirut was bombed and under siege for 89 days, and ultimately Palestinian refugees were massacred at Sabra and Shatila.” Those massacres — he didn’t need to remind an already informed audience — were personally ordered by Ariel Sharon, former prime minister of Israel, founder of the ruling Kadima party and mentor to the current prime minister, Ehud Olmert, who ordered the attacks this year.

According to Idoui, Israel’s repeated attacks on Lebanon “reveal the true nature” of the Jewish state. He said the attack on Arabs in general began in the late 1940’s,when Israel was founded by Jewish militias who systematically uprooted thousands of Palestinian Arabs from their land and, in some cases, wiped entire villages off the map. Many of these people and their descendants “are still refugees,” Idoui added, still living in the squalid “temporary” refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan to which they fled in the first place. Idoui called Israel’s policy towards Palestinians “ethnic cleansing” and added, “It’s still happening in Gaza and the West Bank. It’s the continuation of the process started in 1948.”

Idoui also argued that the United States’ role in all of this is basically as Israel’s enablers, and that U.S. Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice’s talk about the current crisis being “the birth pangs of a new Middle East” is actually part of a long-standing policy by the U.S. and Israel to keep Israel’s Arab neighbors divided and weak. He said that in 1982 the Javits Center worked out a long-term plan for Israel’s security that included “promoting all the tribal divisions” within Lebanon, Syria and Jordan to make sure none of them became strong enough to threaten Israel. “You unleash different forces within the state,” he explained, “one group against another, like in Iraq between Kurds and Arabs, Sunnis and Shi’ites. You create ‘constructive chaos,’ as they call it, by promoting bloody civil wars.”

Keilani, Iraqi-born, focused most of her presentation on postwar Iraq and argued that the chaos in the country today is the direct result of a deliberate U.S. policy. ”I don’t believe the chaos in Iraq today is the result of ‘unintended consequences’ of Bush’s policy,” she said. “I don’t believe it was a ‘mistake’ to destroy every single aspect of Iraq’s society and infrastructure.”

According to Keilani, Iraq today is a nation in virtually complete chaos, comparable to Afghanistan under the Taliban. “Armed militias control the streets,” she said. “The educated middle class has mostly left. There has been a deliberate attempt to target the intellectuals both inside and outside Iraq. Eighty percent of Iraq’s institutions of higher education have been looted or burned to the ground. Iraqis are fleeing to Syria and Jordan. There are no servies. Less than half of all Iraqis have clean water and only eight percent have sewage services. The electrical grid in Iraq under Saddam Hussein was functional and advanced for the Middle East; three and a half years after the U.S. took them over, they still only get electricity 1 1/2 hours a day.”

Since clean water no longer is available through Iraq’s taps, and the virtual lack of electricity makes it impossible to refrigerate food, Keilani explained, Iraqis have to leave their homes every day to buy food, water and ice. This, she said, makes them vulnerable to militia attacks. ”Militias stop buses and make people show their new government-issued ID’s,” Keilani said — and, since the ID’s give the people’s religious and ethnic affiliations, this makes them fair game: a Sunni militia will simply kill everybody on the bus whose card says “Shi’a,” and vice versa.

Among the elements involved in what she described as a deliberate attempt to plunge Iraqi society into chaos and keep it there, Keilani cited the decision by U.S. military forces not to put guards on Iraq’s armories after the occupation — with the result that 250,000 tons of ammunition went missing, much of it, she suspects, now being used to fire on U.S. troops and make improvised explosive devices (IED’s). She also criticized the U.S. for not securing any of Iraq’s government ministries except the oil ministry, for allowing the looting of the Baghdad museum and its irreplaceable collection of antiquities from the founding of civilization in what is now Iraq, and for dissolving the army and police force and putting a blanket ban on members of Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party from holding office or government jobs in the “new Iraq.” She said that as a schoolgirl in Iraq she recalled Ba’ath Party recruiters coming to her classroom to sign up children — and that in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq you couldn’t get a government job without being a party member.

The insurgency, Keilani said, came from these decisions, which created a population of tens of thousands of young men, thrown out of government, the military or the police, with ready access to arms and a major grudge against the occupiers. The U.S.’s solution, she said, was to foment sectarian violence and turn the resistance into a civil war. Among the ways they did this was to set up the Iraqi Governing Council, the advisory group to America’s direct rulers in Iraq in the early days of the occupation, and allocate the 25 seats proportionately on the basis of religion and ethnicity: 13 Shi’ites, five Sunni Arabs, five Kurds, one Maronite Christian and one Turkoman. “These moves were the beginning of the end of Iraqi national unity,” Keilani explained.

Asked just what the U.S. gained from plunging Iraq into chaos and civil war, Keilani said, “At first the insurgency was directed at the U.S. military. Then there were bombings at Sunni or Shi’a mosques, which I don’t think came from any indigenous movement. It divided an otherwise cohesive movement and got these powers to fight each other instead of the U.S. Also, chaos in Baghdad does not influence the oil industry. The U.S. can still pump out oil without metering it, essentially stealing it from the Iraqi people.”

Keilani drew back from an accusation that the U.S. itself bombed both Sunni and Shi’ite mosques to start an Iraqi civil war, but Idoui said the sectarian violence “was in part begun by Ahmad Chalabi and his group, which was supposed to play up the ethnic divisions and play the role of the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan. The people who came in with the U.S. tanks formed death squads, and there seems to have been an attempt to start sectarian violence by bombing Shi’a monuments.” (Chalabi, an Iraqi Shi’ite who fled the country when the British-installed king was overthrown in 1958 and never returned until after the U.S. seized Baghdad, was defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s choice for a ruler for postwar Iraq. He was reportedly responsible for much of the prewar intelligence alleging — falsely — that Saddam Hussein’s regime had weapons of mass destruction, and was later revealed to have been on the payroll of Iran’s secret service.)

Rashmawi, who had been scheduled to begin the meeting but who went on last because his flight was delayed, gave two strongly worded speeches, one in the middle and one at the end, saying the current crisis in the Middle East could only be understood in a geopolitical context. He said that because of its strategic location between Africa and Asia, energy resources, control of the waterways by which oil is shipped to the world and available labor pool, “you cannot be a unipolar power and dominate the world without having clear domination of the Middle East.”

According to Rashmawi, the U.S. currently dominates the Middle East through various mechanisms, including direct colonization (as currently in Iraq), indirect colonization, military regimes and so-called “proxy states.” Among America’s proxy states he listed not only the obvious one, Israel, but also Saudi Arabia and Egypt: Saudi Arabia because it sells oil to the U.S. and its allies at cheap prices in return for U.S. military assistance, and Egypt because it serves as a dumping ground for refugees created by U.S. policies elsewhere. He attributed Israel’s recent attack on Lebanon in part due to the failure of the so-called “Cedar Revolution,” by which Syria was forced out of Lebanon, to create a Lebanese government that would be a viable proxy for the U.S.

“The heart of the liberation movement today is in Egypt, Iraq and Syria,” Rashmawi said. “South Lebanon is a recent failure of the proxy-state policy. They tried to uproot and destroy a homegrown Lebanese resistance movement [Hezbollah] twice, once in 2002 and once in 2006, and now they’re trying to clean up the process by containing their failure. … When you see 3,000 to 5,000 folks able to stand up to the Israeli army and reverse it, two dynamics develop. The first is intensification by the colonists. The second is intensification by the resistance.

Rashmawi said the resistance movement in the Middle East is just a part of a broader anticolonial movement that began after World War II and swept through Africa and Central and South America. He cited Frantz Fanon’s 1961 book The Wretched of the Earth as a source for his analysis of anticolonialism as a worldwide movement that is still going on — and he said that the peace movements in the U.S. and other Western countries need to fish or cut bait: either embrace the anticolonial struggle fully, including support for armed resistance against the colonial power, or remain what he called a “boutique movement” interested more in marketing political merchandise and building influence within mainstream political organizations like the U.S. Democratic party than in supporting fundamental change in the world.

According to Rashmawi, American peace groups take people on tours to areas of struggle, “and you pay $3,000, $4,000 and come back to the U.S. with slides of a tearing mother and a baby just about to die. You know how much I hate that? If it was a photo under the context of liberation, I’d say that child is paying a price that no one should have to pay. But when it’s shown in the context of pity, I hate that. What about a broken flower, a cactus in a broken village, people with rifles working for their own movement? This movement is decontextualized.”

Rashmawi recalled some of his experiences as a part of the A.N.S.W.E.R. (Act Now to Stop War and End Racism) coalition and their attempts to co-sponsor peace events with the liberal United for Peace and Justice (UPJ) coalition until UPJ permanently broke off relations with A.N.S.W.E.R. in 2004. He said that he would be told by UPJ organizers that there were “too many Arabs” or “too many scarved women” in the front lines of joint marches, and that he would have to send the Arabs and Palestinians to the rear of the march so that military veterans or some other group UPJ was trying to promote would be in front. Most importantly, Rashmawi said, A.N.S.W.E.R. insisted that the issue of freedom for Palestine and ending the Israeli occupation be “front and center” in all the demonstrations — while UPJ refused to make ending the occupation of Palestine a demand in its actions at all. According to Rashmawi, the current U.S. peace movement is “married to the Democratic Party” — and thereby cut off from the worldwide anticolonial struggle that alone can bring peace to the Middle East and justice to the world.

Queer Demos Make Busby for Congress a Priority Campaign

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

“You still love me! Thank you!” said an exuberant Francine Busby, Democratic candidate against Republican incumbent Brian Bilbray in the 50th Congressional district, to the predominantly Queer San Diego Democratic Club August 24. Despite her disappointing loss to Bilbray in the June 6 runoff to replace Randy “Duke” Cunningham — who was driven from the seat when he pleaded guilty to accepting millions of dollars’ worth of gifts from lobbyists in the biggest corruption scandal involving a single Congressmember in U.S. history — Busby is the Democratic nominee against Bilbray in the regular election November 7. “I have a lot of work to do, and I’m still fighting,” she said.

“This country is no better now than it was in April [when Busby led the field in the first round of the special election but failed to win a majority],” Busby told the club. “It’s no safer than it was in June. The polls are saying that the rest of the country is waking up to the fact that Iraq has nothing to do with terrorism and debt is just as bad when it’s Republican as when it’s Democratic. People are waking up.”

And, Busby added, she’s confident that enlightenment is coming even to voters in as heavily Republican an area as the 50th district. “The fact that 45 percent of the people voted for me is proof of how anxious they are to get rid of [Bilbray],” she said. “Ninety percent of the Republicans didn’t vote and 45 percent voted for someone other than Bilbray. Businesspeople are not that happy with him because his only two issues are the Mt. Soledad cross and illegal immigration. Businesspeople are against illegal immigration but they also want a guest worker program,” which Bilbray opposes.

According to Busby, the combination of voter dissatisfaction with Bilbray and the makings of an overall “Democratic year” makes her race winnable despite her defeat in their initial matchup in June. She cited a nationwide map of Congressional districts published by the New York Times which changed her district “ from solid ruby-red to pink” — indicating it was still “leaning” Republican but was winnable by a Democrat. She’s also hoping for a fair chance to present her views without the nasty campaigns both the Republican and Democratic Congressional campaign committees ran last time.

Busby’s impassioned speech won her what she most wanted from the club: status as a “priority race” in November, as she had had in June. A priority race for the San Diego Democratic Club is one for which they make a special effort to raise money, volunteers and publicity. Prior to the August 24 meeting the club had designated two campaigns as priorities: Phil Angelides’ race against Arnold Schwarzenegger for governor and openly Gay Chula Vista mayor Steve Padilla’s re-election bid. On August 24, they added Busby’s race and also no on Proposition 85, the latest attempt to weaken California’s pro-choice abortion laws by requiring minors to notify their parents if they intend to have an abortion.

Though she really didn’t need to — the club had already endorsed against 85 and prioritized it before she spoke — Caroline Desert of San Diego Planned Parenthood laid out the case against the measure. “Proposition 85 is unrealistic, unnecessary and dangerous,” Desert explained. “Three out of five teenage girls already talk to their parents about their abortion decision, and the others don’t because they fear for their safety or being kicked out of their homes.” She called Proposition 85 “part of a larger strategy to chip away at choice,” and added, “We cannot mandate parent-child communication.”

Desert acknowledged that the drafters of 85 had eliminated the worst feature of the previous parental notification initiative, Proposition 73 — defeated in the statewide special election in November 2005 — that would have written into the California constitution a definition of life as beginning at conception, which could have been read as automatically banning abortion in the state if Roe v. Wade is overturned. But she described the differences between 73 and 85 as “just superficial and mostly minor changes in language.”

In addition to Busby, the club also heard from various Democratic candidates for office, including one of the most controversial: Maxine Sherard, an African-American woman and retired professor who won the nomination against two-term Republican Shirley Horton in the 78th Assembly District. Sherard’s appearance was a fence-mending expedition aimed at reassuring the membership that she “will have an open-door policy” as an Assemblymember and has a Transgender person on her staff.

But the club received her coolly, partly because of a leaflet placed on people’s seats before they came in. It was a reproduction of an ad Sherard’s campaign placed in the February 2004 Philippine Village Voice during a previous campaign for the seat. The ad, which was in Tagalog — though whoever reproduced it provided an English translation — showed two other candidates with their families, said they supported “women marrying women and men marrying men,” and added that “according to Dr. Maxine Sherard this should not be allowed. Why? Because the Filipino culture and Catholic Religion says marriage is sacred. Marriage should be defined as between a man and a woman. This is what God told us through Adam and Eve: ‘Go and multiply.’”

The club also heard from Alejandra Sotero Solis, candidate for mayor of National City and a former staff member for Assemblymembers Lori Saldaña and Judy Chiu; and Patty Chavez, candidate for Chula Vista City Council. “I started out like the rest of you, fighting graffiti, traffic and crime,” she said. “I started the Adopt-a-Park program, and as a City Councilmember I have continued to roll up my sleeves and get things done.” The club agreed to endorse Chavez after the unsuccessful primary candidate the club had supported before, Pat Moriarty, announced that she’s not only endorsing Chavez in the general election but is working on her campaign team.

The only potential glitch for Chavez came over an answer she gave on the club’s issues questionnaire that she was “undecided” on whether or not the state should require married women seeking abortions to notify their husbands. Asked why she had given this answer, Chavez said, “I took it back to my marriage. I have three children, and as soon as I got pregnant it was about our marriage.” After a follow-up question, though, she conceded that as a matter of public policy “we shouldn’t be regulating anything” on this issue.

In addition to endorsing no on Proposition 85, the club also endorsed yes votes on two other statewide ballot measures: Proposition 84, a bond measure to invest in water quality and safety projects; and Proposition 87, a tax on petroleum products to find alternative energy. The club put off discussion of many of the most controversial measures on the ballot — including Propositions 1A through 1E, Governor Schwarzenegger’s infrastructure bonds; Proposition 83, a toughening of California’s already strict reporting and residency requirements for convicted sex offenders; Proposition 86, a tax on cigarettes to fund hospitals and emergency medical services; Proposition 89, a so-called “clean money option” for publicly funding political campaigns similar to laws already in place in Arizona and Maine; and Proposition 90, an attempt to restrict state and local governments’ right to take private property via eminent domain.

Cygnet’s Wonderful, Wonderful Copenhagen

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

On Sunday, September 25, 1941, Werner Heisenberg, the most prestigious and internationally regarded physicist left in Nazi Germany and the head of the Nazis’ atomic weapons program, traveled to Copenhagen in Nazi-occupied Denmark, ostensibly to lecture at a Nazi-dominated scientific institute in the city but actually to visit his old friend, colleague and mentor, Niels Bohr. Heisenberg stayed in Copenhagen one week and saw Bohr on at least three occasions, but on one of those meetings their conversation was so explosive that Bohr returned home angry and told his wife Margarethe that he never wanted to see Heisenberg again. Exactly what went on between them during that week is a secret both men took to their graves — though Heisenberg and Bohr each offered contradictory accounts of it in interviews, statements and letters after the war — but it was from this raw material that British playwright Michael Frayn fashioned his 1998 play Copenhagen, playing through September 24 at the Cygnet Theatre, 6663 El Cajon Boulevard.

Frayn’s script doesn’t offer his own re-creation of what happened that fateful evening in Copenhagen on which Bohr and Heisenberg went for a walk as bosom buddies and came back furious with each other. Instead it plays fast and loose with the time frame and even shows Bohr and Heisenberg continuing on with their arguments after both men and Bohr’s wife —a third on-stage character and frequently the voice of reason between them even though all she knows about science is what she’s picked up from the manuscripts she’s typed for her husband — are all dead. (It’s hard to believe that if there is an afterlife and Bohr and Heisenberg made it there, they wouldn’t spend at least part of their time trying to reason out the physics of their current state of existence and reconcile those with the discoveries they made in this world.)

What results is a marvelous, if rather talky, play about the obvious dilemma facing both the proudly nationalistic German Heisenberg and the half-Jewish Dane Bohr: how to reconcile one’s calling as a scientist with one’s duty as a human being, and whether scientists ought to be held morally accountable for the consequences of their discoveries and hold back from certain lines of research that might have destructive consequences. It’s also about more than that: it’s about the thickets of contradictions Heisenberg, whose greatest contribution to science was the discovery of the so-called “uncertainty principle” at the heart of quantum physics, created in his public statements about his wartime role, and the irony that a man famous for explaining the universe as based on “uncertainty” would leave behind so many uncertainties about himself. And it’s a script that questions the common notion that scientists do their best work in close collaboration, or at least communication, with each other; in one of Frayn’s quirkiest and most moving moments, both Heisenberg and Bohr admit that their greatest insights came to them while they were totally alone in isolated environments that gave them a chance to think without distractions.

Even before Frayn wrote his play, the Copenhagen meeting(s) between Heisenberg and Bohr had taken on an almost mythical significance in the history of World War II and the role atomic weapons played in it. In the late 1930’s, Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, both pacifists, Jews, and refugees from Nazi Germany, put aside their anti-war convictions and lobbied President Franklin Roosevelt to start a nuclear weapons program for fear that the Nazis were also working on such research — and if the Germans got the bomb before we did, given Hitler’s known record of brutality, he would use it to destroy whole cities, or even nations, and establish the “Thousand-Year Reich” of which he boasted. Ironically, Hitler’s bomb program was hobbled from the get-go by his racism; before Hitler took power Germany had been the world’s leader in theoretical physics — but most of those physicists were Jews and, smart enough to see the handwriting on the wall, left as soon as they could. Eventually most of the German physics community relocated to the U.S. and worked on the Manhattan Project, which gave the U.S. the world’s first nuclear weapon — and Bohr joined them as soon as he got out of Denmark in 1943, first to neutral Sweden and ultimately to the U.S.

Frayn takes all these facts and uses them to construct a somber, compelling meditation on the responsibilities of scientists, especially but not only in wartime. His play examines one of the great unanswered questions about Heisenberg — did he fail to build a bomb because he deliberately sabotaged the German nuclear program out of horror at what the Nazis would do with it, or did he simply get the science wrong and decide a bomb was impractical? It also questions whether Heisenberg, who confined his actual work to building an experimental nuclear reactor for energy and medical uses — though one which could also have made plutonium, which could have been used in a nuclear weapon instead of enriched uranium (and was in the bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima) — was really morally superior to Bohr, who did work on a weapons program that manufactured atomic bombs that were used to destroy two cities. The currency of these issues was hammered home when on August 26, the day Cygnet’s production of Copenhagen opened, the Associated Press announced that, dodging international attempts to stop them from enriching uranium, Iran was going to build a heavy-water reactor that would allow them to use ordinary, unenriched uranium to generate power — and to create plutonium to fuel a nuclear weapon. This is the same kind of reactor Heisenberg was designing for the Nazis.

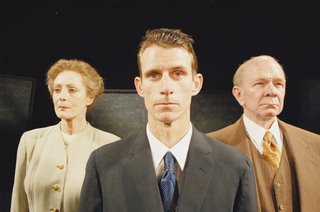

Cygnet Theatre gives Copenhagen a first-rate production. Jim Chovick stands out as Bohr; his age and overall appearance perfectly suit him to play an eminence grise but he’s also spry enough to catch the nervous, fidgety energy of a character who seems unable to sit still for more than a few seconds at a time. Rosina Reynolds as Margarethe turns out to be as good an actress as she is a director; superbly aged by Cygnet’s (uncredited) makeup artist, she’s not only effective as the materfamilias who holds her rambunctious, hot-tempered husband in place — in Frayn’s script Heisenberg calls their family an atom, with her as the stable nucleus and him as the randomly mobile electron — she also does a good job as the representative of all us non-scientists in the audience trying to make sense of what her husband and his equally abstruse friend are saying. Cygnet regular Joshua Everett Johnson is too young-looking for Heisenberg — one wouldn’t believe that this man turned 40 just three months after the Copenhagen meeting, and it seems odd that the makeup people who so effectively aged Reynolds didn’t give him a similar treatment — but otherwise his performance is great, ably portraying both Heisenberg’s misgivings and his rationalizations.

Director George Yé, faced with an unusually long (the first act is 80 minutes, the second an hour) script that’s basically three people talking in a room, solves the obvious problem of avoiding boredom by keeping the actors, Chovick especially, in almost constant motion and having them spit out Frayn’s dialogue so fast they have to lose themselves in their characters merely to keep up the pace. Yé also did his own sound design, which effectively mixes in music at the start and finish of each act — though the opening sound effect of Nazi forces marching through the streets of Copenhagen should have been “panned” across the theatre instead of remaining in one place aurally. The set by Sean Murray, Cygnet’s artistic director, is simple: just three chairs and a black backdrop in front of which are hung blackboards with mathematical equations — and lighting designer Eric Lotze creates a powerful effect towards the end when he uses the center blackboard as a screen on which to project the so-called “diffusion equation” which proved an atom bomb would work.

Copenhagen is a powerful drama that plays to the strengths of the Cygnet Theatre: incisive direction, strong character portrayals, excellent physical production. It’s not exactly a good-time piece, but it has its moments of humor. On opening night, when Bohr announced early on that he’d co-written a paper that conclusively proved it would not be possible to build an atomic bomb, the audience laughed at how wrong he turned out to be — but also with the mixed feeling of how much better off the world would have been if he’d been right.

Copenhagen plays through Sunday, September 24 at the Cygnet Theatre, 6663 El Cajon Boulevard, Suite N. Performances are at 8 p.m. Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, 2 and 7 p.m. Sundays. The Sunday, September 10, 2 p.m. show will feature a post-show discussion led by Herbert York, American nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project. Tickets are $25 Thursday and Sunday evenings, $27 Friday evening and Sunday matinee, $29 Saturday, and can be purchased by calling (619) 337-1525 x3 or online at www.cygnettheatre.com

Middle East Peace Demo Draws 400

Speakers Bash Israel, Praise Hezbollah Resistance

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

A surprisingly high turnout of 400 people came out on warm Saturday, August 12 to Balboa Park to stage an action protesting Israel’s attack on southern Lebanon and continued occupation of historic Palestine. The crowd was evenly distributed between Arab and Muslim Americans, many of them in traditional Islamic clothing and carrying Lebanese, Palestinian and Iraqi flags, and mostly white peace activists. The event began with a gathering and a few speeches via a bullhorn at the fountain at the Park Boulevard side of the park, then included a march across the park to Sixth and Laurel, where a longer rally took place at the end.

Many participants in the march themselves seemed surprised at the size of the crowd. One local journalist covering the event said he’d got e-mails from four different Muslim organizations in San Diego. “I didn’t know there were that many!” he said. But at least one local peace activist said she was concerned about the foreign flags being carried by many participants and the Muslim garb some of them were wearing. She explained that the protests to protect the rights of undocumented immigrants only began attracting popular support once the participants began carrying U.S. flags and dressing like ordinary U.S. residents.

While the official theme of the march was peace and a call for Israel to withdraw from Lebanon, some of the participants took it farther. During part of the march, its leaders started chants actively supporting the Hamas and Hezbollah movements and the resistance to the U.S. occupation in Iraq. Later, when rally MC Carl Muhammad — not an Arab or Middle Easterner but an African-American activist with the San Diego branch of the International Action Center (IAC) — mentioned that some of the 10 counter-demonstrators on Laurel had carried signs reading, “Go get ’em, Israel!,” one member of the crowd responded by yelling out, “Go get ’em, Hezbollah!”

Like the participants, the speakers were more or less evenly divided between mostly white peace activists and Arab and Muslim Americans. The event was opened by a speaker identified only as Walid, who said, “Your presence here today as people of conscience is crucial to oppose the atrocities being committed by Israelis on Palestinians and Lebanese. One thousand Lebanese have been killed [in the current war] and hundreds of thousands have been made homeless. Lebanon has been bombed into smithereens. The Israelis deliberately attacked civilians in convoys, massacred women and children, and killed farm workers.”

Walid also noted the situation in Gaza, the Palestinian territory Israel supposedly “withdrew” from last year, which they invaded before they attacked Lebanon and under the same pretext: to “rescue” an Israeli soldier taken prisoner by resistance forces. “In Gaza, the daily shellings continue and more than 160 women and children have been killed in the last month alone,” he said. “This is the epitome of injustice, all paid for by our tax dollars in violation of our laws. We need to send a powerful message to our government that human life is not cheap, all life is sacred and we need to stop funding the war machine.”

Though the rally took place one day after the United Nations announced an agreement for a cease-fire in Lebanon, participants clearly regarded this resolution as a sham. Rebecca Anshell of the International Socialist Organization (ISO) explained that “the so-called ‘cease-fire’ calls for Hezbollah to disarm and allows Israel to ‘defend itself,’ which means they can continue too destroy Lebanon and kill Lebanese.” She didn’t need to explain to her audience that Israel and its apologists had justified all their recent actions in Lebanon and Gaza by calling them “self-defense.”

Noting that the Bush administration has openly taken Israel’s side in the current conflict, Anshell added that secretary of state “Condoleeza Rice calls this ‘the birth pangs of a new Middle East.’ This is a really forthright statement of the goal of the war on terror: to create new market structures in the Middle East to decide who gets oil and keep China or India from becoming a superpower. Israel has been the U.S.’s agent and is doing its dirty work. … It is our job as activists to explain the way the occupations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine and Lebanon are part of a broader strategy. We have to take action against the whole agenda and unite people in the U.S. against this racist war.”

A number of speakers made the connection between Zionism and racism, but fewer more strongly than Jewish poet Steve Kowit. He was called to read his poem Intifada, which he’d also read at the Hiroshima Day peace demonstration at the Embarcadero six days before. But as he introduced the poem — which compares Israel’s oppression of the Palestinians to that suffered by the Jews throughout Europe and most of the world for the previous 1,600 years — he cited a book called Apartheid Israel by Uri Davis and said Israel has been the world’s most racist country since the apartheid system in South Africa was abolished.

“Ninety-three percent of Israel is reserved by law for the exclusive use of the Jewish people,” Kowit said. “If that isn’t the very definition of racism and apartheid, there is no such thing as racism. Israel stole the Palestinian homeland in 1947, 1948 and 1967, and now they talk about giving back a tiny bit of it and calling it the ‘Palestinian state.’ … The laws [in Israel] are designed to allow Jews to control the whole country and keep everyone else from being able to make a living.”

Zahid Mamouni of Al-Awda San Diego, the local branch of an international movement to demand that Palestinians be allowed to return to their former homelands inside Israel — a call fiercely resisted by virtually all Israeli politicians because it would mean the end of Israel’s Jewish majority — pointed out the disproportionality between the alleged provocations for Israel’s invasions of Lebanon and Gaza and Israel’s actual actions. “There was one prisoner of war in Gaza, and as a consequence 135 Palestinians are dead, 245 are injured and most Gaza residents are deprived of electricity, water and medical supplies,” he said. “In Lebanon, [there were] two Zionist POW’s, more than 1,000 Lebanese killed, 3,500 injured and hundreds of thousands displaced.” He called on members of the crowd to contribute to emergency relief funds being set up by Al-Awda to help people who’ve lost their homes due to the attacks.

“We need to liberate America from this fascist President and his group,” said Sheikh Sharib Wafiq. “Bush says the resisters in Palestine, Lebanon and Iraq are terrorists. But if someone invades our land, we will fight. Our duty is to resist. It’s very important to support our brothers in Iraq, in Lebanon, in Palestine. This is our duty. It’s very important for us as Americans to raise our voices. I hope San Diegans will stand with us. I hope we will have thousands at our next demonstration. It’s very important to vote against the criminals. God loves peace, and there is no peach without justice. And there is no justice without an end to the occupation of Palestine, Lebanon and Iraq, and without giving all the people their freedom. We pray for peace because we like peace and justice. May God support all the people under occupation, the people in Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq and our people here in America to liberate themselves from the lies of the mass media.”

100 Attend Annual Hiroshima Day March and Vigil

Speaker Accuses U.S. of Deliberately Depopulating Earth

by MARK GABRISH CONLAN

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Gabrish Conlan for Zenger’s Newsmagazine • All rights reserved

Before a crowd of 100 people outside the U.S.S. Midway museum on the Embarcadero downtown, Berkeley-based anti-nuclear scientist and activist Leuren Moret accused the U.S. government and the “vested interests” who control it of deliberately using nuclear weapons, including depleted uranium, to cut the world’s total population in half. Moret, an environmental commissioner in the Berkeley city government, president of Scientists for Indigenous People and host of a public-access cable TV show on nuclear issues, said the U.S. government “wants to eliminate two to three billion people” and cited a 30-year-old document as her source.

“This is not a conspiracy theory; this is U.S. national policy,” Moret said. “It’s called Global 2000 and it was written by Henry Kissinger, General Alexander Haig and [former Democratic senator and vice-presidential candidate] Ed Muskie for President Carter. We are in Global 2000 now, and I am convinced that the amount of carpet bombing and grid bombing that started under Clinton in the 1990’s is what Global 2000 is, because certainly the health statistics I have from India, Japan, Britain and the United States support that.”